The Sporting Life: The Typesetters Against the Aristocrats of the Sprint

An Obscure Collision of Sports and Commerce

There’s no shortage of people writing about artificial intelligence, the automation of work, the waxing and waning power of unions, and how it all ties into the preservation of human dignity. We’d probably be happier without work (as we currently understand it), but it will necessarily be messy and drawn out to prove it. Fortunately, Sublime Prosaic is about none of these things, except maybe elliptically. This column about sports and leisure naturally begins with an examination of the (mostly) vanished profession of typesetting.

//

The Typesetters’ Guild, Mergenthaler’s Linotype and The Open Air Book of Sports

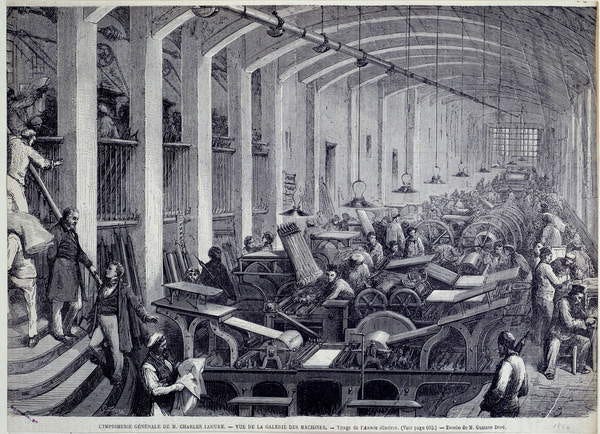

The invention of movable type in the West was a big deal (citation not found). Printmaking with movable type (typesetting) was also labor intensive (tons of letters in tiny cabinet drawers, slotting things in by hand to spell the words to be pressed). We can proceed in our discussion without much more technical detail here. I’ll spare you the exposure to printmaking nonce words like “glyphs,” “flongs,” and “sorts.” Printing as a profession flourished; it created and sustained a new class of specialist laborers for over 400 years in Europe and elsewhere. Like many guilds keeping specialized knowledge, the typesetters of the world went on to create unions.1

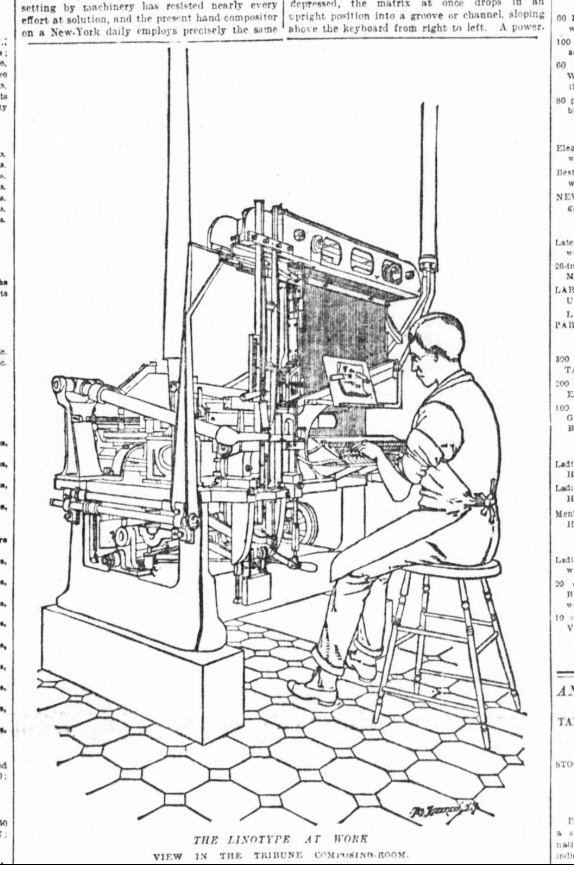

Then the Linotype (so-named for its ability to stamp entire metal lines of type) was invented in 1884 and subsequently perfected around 1886.2 The machine could run with one operator, who would use a kind of keyboard to input the material for typesetting (no more manual assembly of language letter-by-letter). The sequences would be stamped out on hot metal plates, which could then be melted down and reused thousands of times.

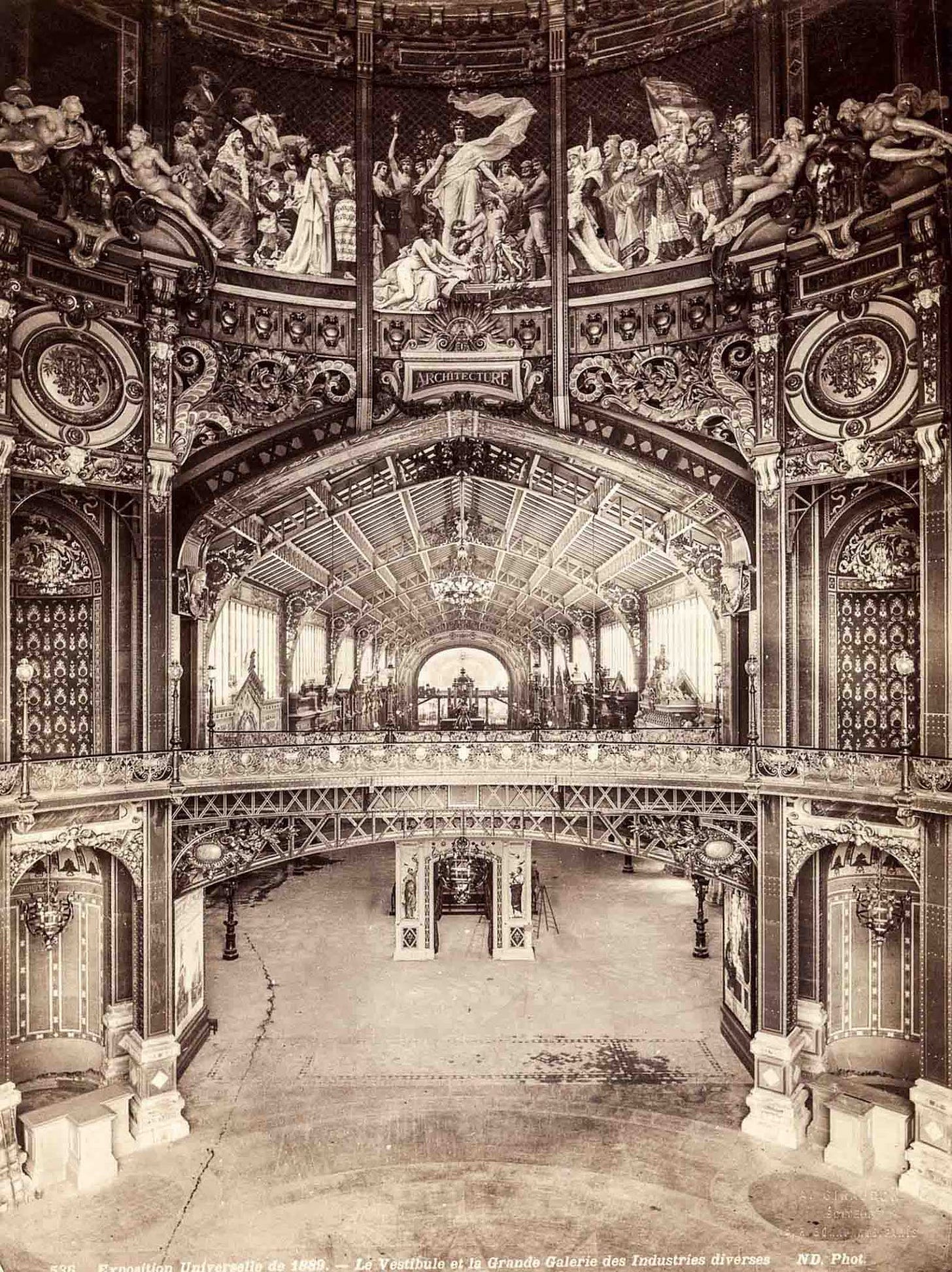

It’s difficult to overstate the impact the Linotype had on the world. But we can see a nice microcosm with the attendees to the 1889 Paris Exhibition, where the Linotype made quite a splash.

As detailed in the dubiously named Anglo-Saxon guide to the Paris Exhibition 1900 (your intended audience will know your guide is printed in English when it turns out they can read it), the Linotype machine was considered “one of the wonders of the century.” As explained to Exhibition attendees, the Linotype was “the outcome of about twelve years of continuous experiment and invention, and the expenditure of a sum of money very nearly approaching a million pounds sterling.” It was also presented to attendees as the most important innovation in printmaking since Gutenberg’s printing press. That’s also true. In the Guide’s words:

It marks the first and only successful departure from the long- established forms of movable type and the primitive methods of hand composition. It is the only machine which is in practical, successful use in any considerable number of printing offices, and the only machine which has effectually withstood the test of time. Many machines and processes were developed by its inventor and his associates, each marking an advance in the art. [...] This raising of the unit of composition from a single letter to a line, the production of each line complete and independent of the others, has proved to be the most radical and important invention in the printing art since the days of Gutenburg, Koster, and Caxton.

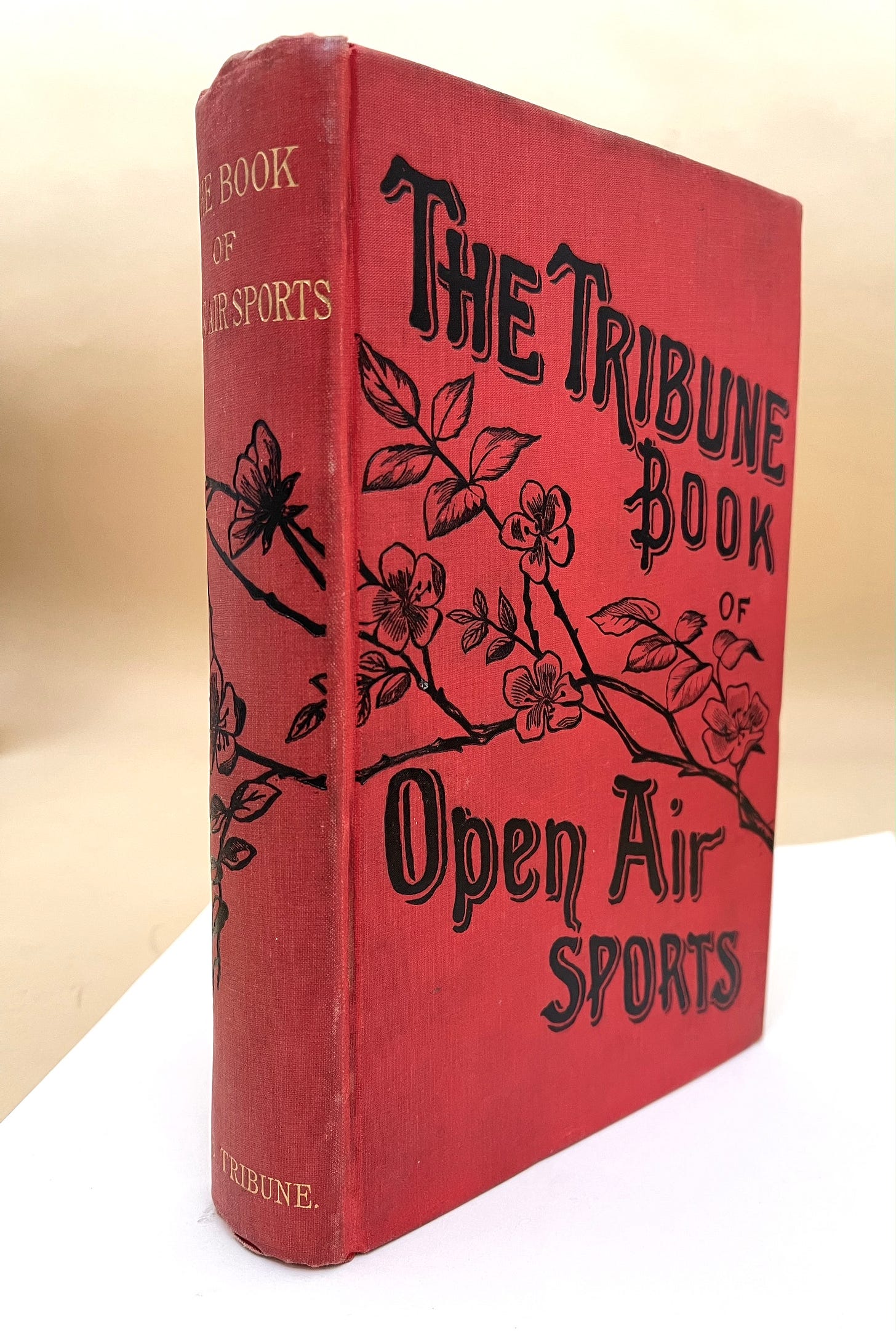

Another curiosity about Linotype finally brings us to sports, in a way. For the avid collector, you can own the world’s first book typeset by Linotype: the whimsically named Book of Open Air Sports (given away in 1886 to those who would agree to a 1-year subscription to The New York Tribune).

The book is also notable to me for its framing of the rise in demand for sports journalism. You can almost hear the exasperation of the editors at the direction the culture is taking:

During the Summer of 1886 The Tribune was compelled to devote more than 500 columns of its valuable space to the Open-Air Sports of the United States, assigning to the collection and presentation of this class of news many of the best observers and writers in its service. Nothing can indicate more clearly than this the place which athletic amusements have taken in this country.

Open-Air Sports have, in fact, within the last few years achieved a wholly new and unprecedented popularity among our people. Twenty years ago a game of baseball or a yacht race seldom attracted any other witnesses than the personal friends of the contestants; whereas, in 1886, we have seen from 10,000 to 15,000 spectators assembled to witness a single game of baseball, - and more than 30,000 people congregated at a yacht race. Henceforward every newspaper which is in accord with the spirit of the times must assign an importance in its columns to Open- Air Sports.

So in 1886, all the best beat reporters were having to spend more and more time and column space in the newspaper writing about “athletic amusements.” And we’ve been paying for it ever since. /s

I’m curious whether this trend has continued—ever increasing shares of media and mindshare devoted to sports? If so, it would back up that Kurt Vonnegut quote people love, and prove that my favorite “sportswriter,” Jon Bois, called it correctly in his 17776 series when he imagined a society that had cured all ills, gained immortality, and decided to, among other things, just play very weird and long football games, forever. If we really are fundamentally creatures of play, not work, then the cure for what’s ailing us is not more “#content,” but games.

The book itself includes large sections on Horsemanship and Yachting, but the newer (for 1886) hobbies of Photography, Camping, Cycling and Fishing receive their own sections, although thinner than some of the others.

The inventor of Linotype, Ottmar Mergenthaler, was a German clockmaker and immigrant to the United States. His invention made rapid printing of newspapers, magazines and all manner of other publications considerably faster, and the Linotype remained one of the standardized means for typesetting until it fell out favor in the 1970s (losing ground to digital and other methods). One account of his life asserts that no daily newspaper could be longer than 8 pages before the adoption of his machine.3

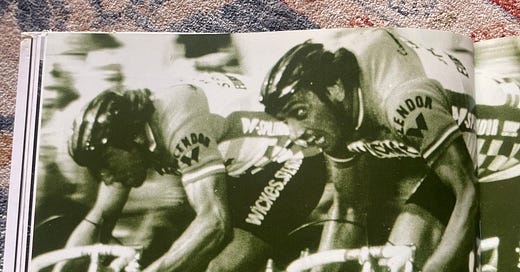

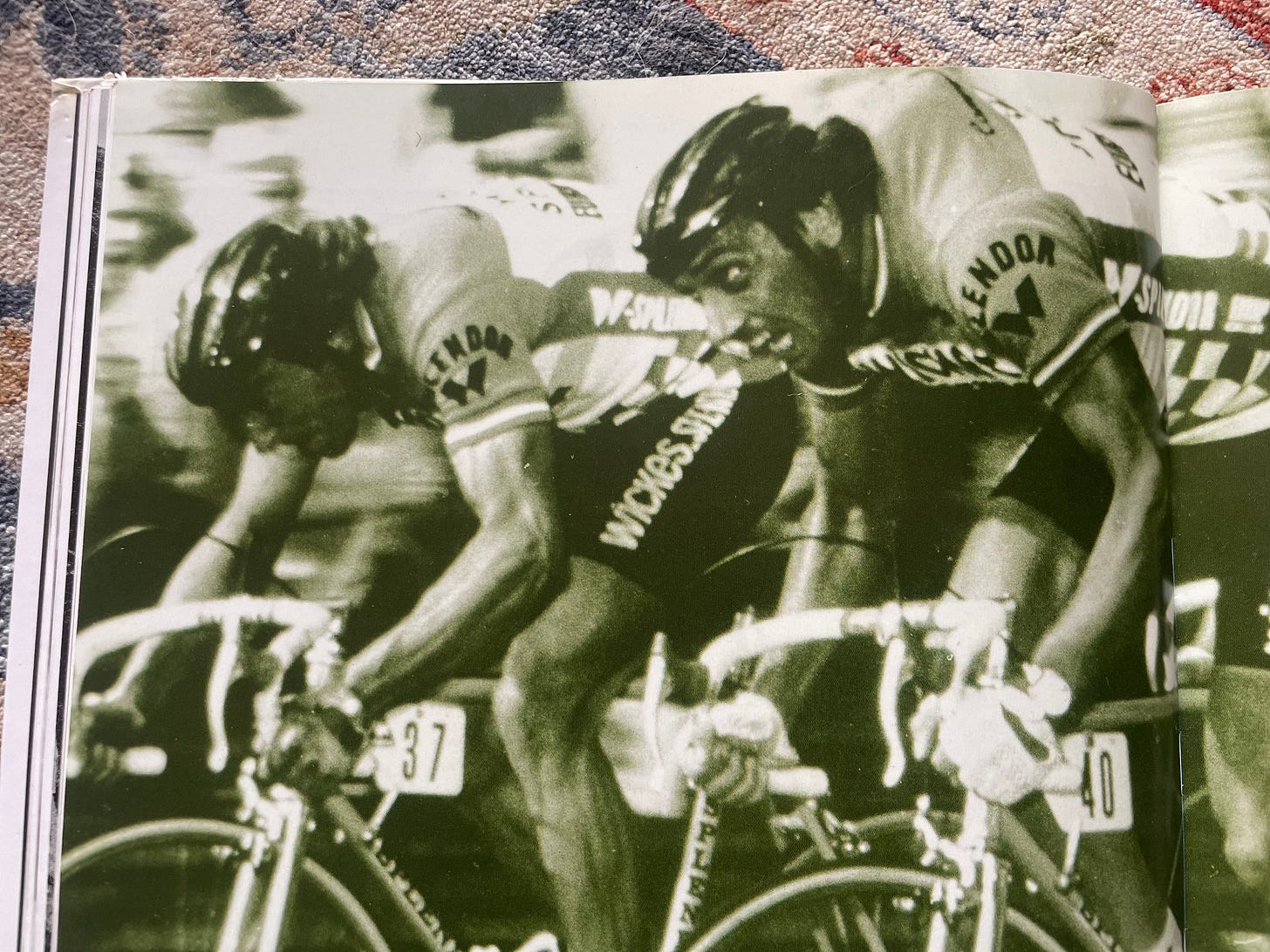

A Sunday in Hell and The 1976 Paris-Roubaix Race

So why am I reading and thinking about Linotype workers? The answer lies in a curious artifact of cycling history. A protest by Linotype operators pops up unexpectedly in the cycling documentary, A Sunday in Hell.4 As a stylish postcard from Paris, 1976, it’s worthing watching just for the aesthetics (cycling fashion never fully recovered from the advent of helmets and the decline in the use of cycling caps). If you don’t have an hour and 45 minutes to watch the documentary, you can just check out the scene below running from 24:50-28:36.

What’s that holding up the start of the race? It’s protesters demonstrating against one of the newspapers that helped organize it: Le Parisien libéré (started in 1944). As the narrator tells us, these workers are from an affiliated printshop and are protesting “against the redundancies of the operators on Linotype as a result of automation.” The narrator explains this is a “longstanding labor conflict,” to the point that the racers and organizers essentially expected something like this.5 The racers end up proceeding single file through a kind of tunnel of protestors (like the Parent Tunnel one might find at a children’s soccer game after the match), while receiving literature and lectures about the “capitalists who have organized their race.” As a further surprise, many of the protestors also have favorites in the race and offer words and gestures of encouragement to the racers.

What is the Paris-Roubaix race? It’s all tidily and wildly summarized from 11:56-13:08 above. With punchy narration and a percussive accompanying track, we are shown the history of the “Flemish Supermen” riding through the “hell of the North,” consisting of “primitive, narrow country roads with centuries old cobblestones.” These absurd stretches, alongside the abandonment of any common sense or instinct of self-preservation in choosing to traverse them by bicycle, makes Paris-Roubaix the “hardest and most fascinating of all classic one day races.” That year’s race (which has been running continuously since 1896, stopping only for the World Wars and COVID) was also sponsored by BNP (National Bank of Paris)—so of course the bank representative gets to stand on the winner’s podium at the end of the race. The winner must also drink a contractually mandated refreshment of mineral water to satisfy the producers of the race (narrator: “there’ll be a bit more hell if he doesn’t like to drink it”). Two last parting shots from the filmmaker at the market interests that make mass sporting events and sporting culture possible, in case a viewer isn’t sure where sympathies lie.

The Aristocrats of the Sprint

Cycling, with Eurocentric roots, has a long history of labor action interruptions, as it turns out. A moderator of the r/peloton subreddit has enriched us all with a kind of running catalog: Protesting Amid the Peloton - A Selected History of Political Interruptions at the Tour de France. The throng of spectators makes sporting events generally a perfect place for these sorts of performances (whether that’s Bong Hits for Jesus, streaking or demanding that your work not be replaced by a machine).

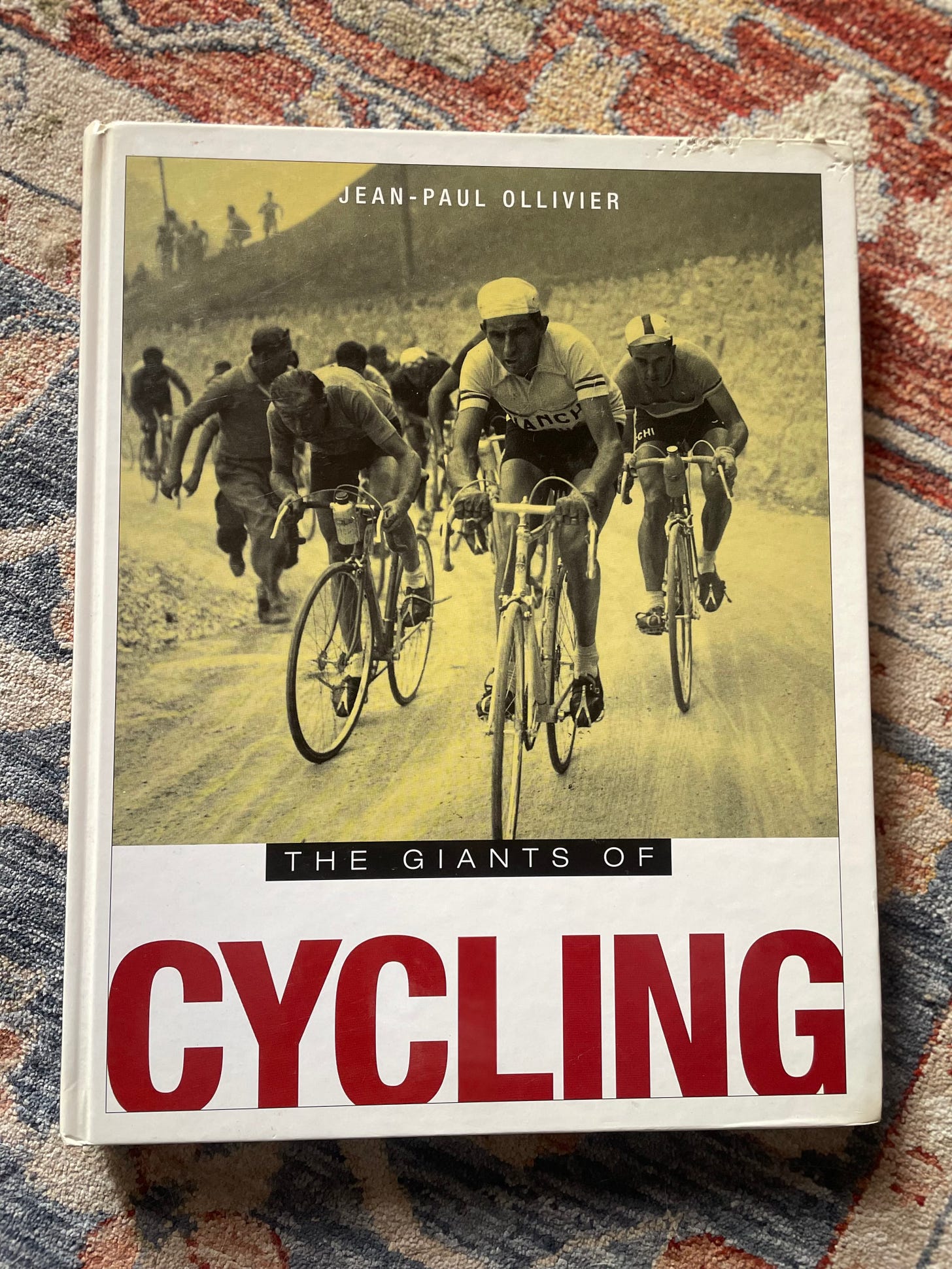

There’s a lot about the history of cycling I’m still learning. The inspiration for this article’s title came from a coffee table book I received as a gift. The Giants of Cycling, by French historian Jean-Paul Ollivier, is a book full of portraits and action shots of famous cyclists. The profiles include moving prose, anecdotes, and the very excellent nicknames (real, imagined?) of the cyclists. The names can be obscure, funny, forceful. Jean Robic: Leather Head; Raphael Geminiani: The Big Rifle; André Darrigade: The Greyhound of the Landes; Bernard Hinault: The Magnificent Badger. All fascinating in their own way. It’s fun to imagine a commentator yelling these things in French.

The chapters and organization of the book are disorienting to me. Each chapter is a seemingly random mix of old and new cyclists, organized by chapter concepts I have trouble distinguishing: ‘The Legends,’ ‘Cyclists of History,’ ‘The Heroic Ones,’ ‘The Winged Gods,’ and ‘The Classics.’ It seems to me like a ‘Cyclist of History’ could easily belong in the chapter ‘The Classics’ or ‘The Legends.’ How do you choose? I barely know what I’m reading half the time in this book.

And then there’s a chapter the author has titled ‘Aristocrats of the Sprint.’ Ollivier opens this chapter with a saying that I’ve puzzled over a good deal:

Just as speed is the aristocracy of movement, so it makes sense in our eyes to present the sprinters as the aristocrats of the cycling peloton…

It’s stated as simply as that, with no additional explanation regarding that first bit. As a statement, “speed is the aristocracy of movement” is very good. I can only guess as to what it means. Perhaps it corresponds to some common/famous aphorism in French (or in cycling history commentary), and it loses some of its character in the translation to English.

Part of my selection of this phrase for this piece’s title is the irresistible, but surface-level, classist overtones of the sporting “aristocrats” versus the striking laborers. It would be lazy to present them as being in actual conflict—they are quite alike. Both racers and typesetters are manual laborers (performing repetitive, physical tasks). And it’s here that leisure and market forces collide. In the context of the Paris-Roubaix race, cyclist and striker alike are set in motion and striving against the demands of the same economic flywheel. Without the newspaper (and the proliferation of print enabled by Linotype operators), there’s no race or racers that anyone would bother sponsoring, and then no appreciable number of spectators. In this, we can see the echoes of The New York Tribune’s 1886 lament. It’s an ongoing state of affairs. While this class of cycling royalty (and ensuing media coverage) is still with us, the same cannot be said of the typesetters.

Past Tense

I learned about the demise of the typesetters union with the same sense of melancholy you might experience reading about updates to the endangered species list. I opened the Wikipedia article hoping to discover some unlikely confluence of factors resulting in the union holding out against modernity (like the surreal experience of still being able to order a telegraph). The first sentence: “[t]he International Typographical Union (ITU) was a US trade union for the printing trade for newspapers and other media” (emphasis mine). Oh no, past tense.

The rest of the Wikipedia article doesn’t get much better. Maybe it was my writing about obituaries last week, but now an obituary for a trade organization seems like it can contain magnitudes more loss (with many more lives and livelihoods caught up in the impact). From the Associated Press on December 31, 1986, from Colorado Springs, CO:

The International Typographical Union has ceased to exist, and most of its staff was laid off at national headquarters here. Most of the 60 workers are continuing on a temporary basis with the Communication Workers of America, with which the ITU merged, said ITU spokesman Bill Frazee. The ITU ended operations on December 31, 1986. On January 1, 1987, the union joined the CWA as its Printing, Publishing and Media Workers Sector. CWA has its headquarters in Washington, D.C., and employees working for the sector will transfer there in two to four months, Frazee said. The International Typographical Union was the nation's oldest union, charted nationally in 1852. Its membership peaked in the 1960s at 100,000 printers. But since computerization of the business, membership has dropped to 40,000 working printers and 35,000 retirees.

Was typesetting a good job? One detailed look at the machines notes an unfortunate “feature,” a hazard to the operator:

Another unique feature of the Linotype machine occasionally occurred when a squirt of molten-lead, which didn’t have any odor, spraying out through gaps of loose matrices, became hazardous to the operator. That’s when he grabbed the so-called “Hell Bucket” to capture the flowing menace. It was called the “Hell Bucket” because it would often “go to hell” and melt from the molten lead.

Handling buckets of hot lead, it turns out the typsetters had their own Sundays in hell! So what was lost? Did this profession endow its practitioners with a sense of satisfaction and meaning? Probably not (outside of a stable income and benefits), and it’s strange to mourn the demise of a machine that itself displaced practitioners of the earlier manual typesetting trade. But it’s all beside the point now.6

Manual and customized typesetting lives on in niche trades and applications.7 For example, Aardvark Letterpress in Los Angeles made my business cards (and I am in possession of the metal plate they struck/used to produce them). These purveyors of printmaking practice in a vanishing art. I still love a good wedding invitation suite that goes to the trouble of employing a printmaker (embossing, letterpress, the purposeful selection of a paper’s weight and grain—where else can you still feel these things in hand?). As for the object of the 1976 French Linotype workers’ protest, Le Parisien libéré? It’s still in operation today, but is owned by Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, the “world leader in high quality products.”

At least we’ll always have Paris(-Roubaix). Please be sure to drink and enjoy your mineral water.

//

Happenings

The gardening zeitgeist is moving from drought-tolerant succulents to native plants in a lot of places. Theodore Payne Foundation’s 21st anniversary home/garden tour is approaching (April 15-16, 2024). Only mentioning it now as sponsor sign ups are open. $500 for a sponsorship and it seems like a good opportunity to address a very targeted market. No sponsorship for Sublime Prosaic this year, but working on a native garden plan for our front yard (so maybe I want my yard on the tour itself).

Natural History Museum, London has announced its winners for Wildlife Photographer of the Year, 2023. The 60th anniversary competition opened for new entries on Monday, October 16, 2023.

To Read/Watch

Certainly didn’t intend to cover the Vesuvius Challenge on some kind of regular basis, but a few days after I posted the link showing the University of Kentucky’s ongoing efforts, researchers now have their first word from scanning the carbonized scrolls: “πορφύραc” or “purple.”

A very good article from the Los Angeles Times showcasing a Southern California garden full of natives and herbs.

NYT is here with a new entry in their ceramic food beat. As with dusty green bottles of chartreuse, people should raid their grandparents’ second homes for good Trompe l’oeil.

Still waiting for those think pieces on Bill Watterson and John Kascht’s The Mysteries, but it’s possible this is a piece of art that defies the usual processes by which the internet picks something up and propagates opinions about it (I’m enjoying the 1 star Amazon reviews in the meantime). The good news is Watterson and Kascht released a charmingly self-effacing video discussing the project themselves (in which Watterson describes the book as having “no audience” and being “unillustratable”). In working with Kascht, Watterson wanted “pictures that didn’t show things for a story that didn’t say things — which was probably the aspect of the book [Watterson] liked the best…” The two go on to discuss their years-long collaborative process, one Kascht describes as “appallingly inefficient and wasteful, we were basically drawing the map as we wandered around lost.” So it’s a charming, deceptively simple little book that hides an incredible amount of intellectual and artistic labor. I like it.

I’ll play myself off with an all time great clip from The Onion that needs no introduction. Whatever you’re doing in life, I hope it’s not feeling like the functional equivalent of this man’s scholarly work on anteaters.

Alongside such other unions emblematic of the time, like the Cigarmakers Union.

I always like a footnote functioning literally. Here, we make passing reference to (i) an unsuccessful infringement case in 1893 brought by Rogers Typograph Company against Mergenthaler for use of “the so-called Schucker’s spacing device” (Rogers would later be acquired by the Mergenthaler Linotype Company in 1895, buying out the patent) and (ii) to the Paige Compositor, another failed competitor to Mergenthaler’s Linotype machine, notable now only for Mark Twain’s involvement as a major investor. He committed seven million dollars in today’s money to the endeavor, including the majority of his wife’s inheritance. Through legal maneuvering, Twain’s wife was named as one of his “preferred creditors” in his subsequent bankruptcy. The failure of the Paige Compositor is also sometimes speculatively blamed for a decline in the quality of Twain’s writing and humorous style.

This account also reveals he dies of tuberculosis at the age of 45 in Baltimore, but only after his recently completed manuscript for his autobiography was incinerated when his house in New Mexico (where had been living to help treat his consumption) burned down. His life would make a great movie, albeit as a dark comedy. From his brief NYT obituary, October 29, 1899: “Mr. Mergenthaler naturally profited greatly by his invention and became a rich man, though he did not receive the proportion of the profits, to which, in his opinion, he was entitled.”

A Sunday in Hell is directed by Jørgen Leth, of Det perfekte menneske (The Perfect Human) fame. Great short film from 1968. It’s on YouTube and you may want to smoke a pipe afterwards.

The Workers Bush Telegraph has an excellent summary of the labor dispute at the core of what we see in the documentary.

A 2013 French law now requires a complex negotiation process in order to pursue lay offs at companies with more than 50 employees. Given how often they are willing to go on strike (something still rare, even stigmatized in the United States), French labor action is just different.