The Sporting Life: The Ecstasy of Le Globe Aérostatique

An Abridged History of Ballomanie (and the Jaguar Medicine Men of Peru)

We’ll be camping in New Mexico this weekend and the trip is framed by a certain steampunk sensibility. We’re arriving by train (Amtrak from Los Angeles to Albuquerque, where we pick up our camping van), and then we’re going to attempt dragging our children to watch the mass ascension of hot air balloons that makes the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta famous.

It’s hard to properly communicate how important hot air balloons were to people when they were first created. It only gets more interesting when one considers how thoroughly relegated to the ash heap of popular imagination balloons are now (two centuries later, they are languishing in obscurity beneath the perpetual joke of the dirigible).

//

I. Gonesse with the Wind

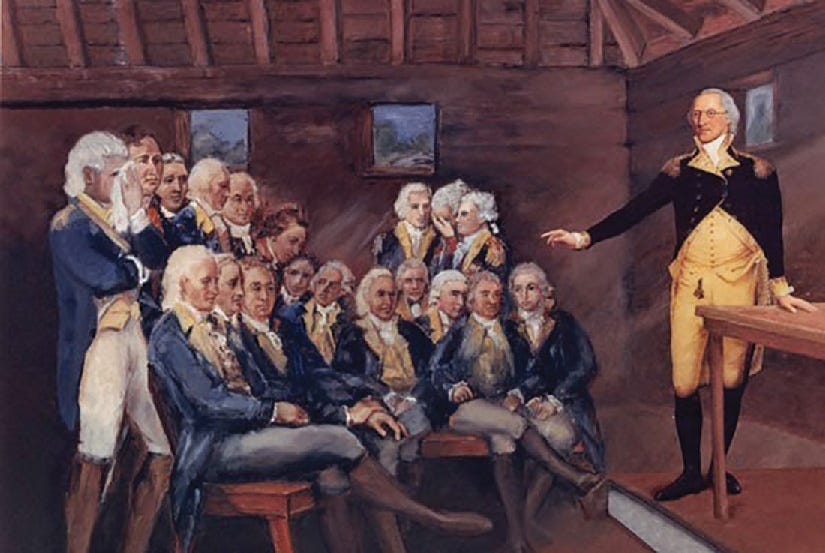

In 1783, George Washington met with veterans of the Revolutionary War in Newburgh, New York and asked them to hold off on rioting just a little bit longer (it was more of a military coup/nascent insurrection in progress) in order for their overdue wages to finally get paid by Congress. In Washington’s plea to the soldiers not to choose violence (which would complicate the ongoing work on a treaty in Paris to the end the war and secure recognition of America as a sovereign nation), he resorted to a bit of prop work that reportedly moved his listeners to tears:

“Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for, I have grown not only gray, but almost blind in the service of my country.”

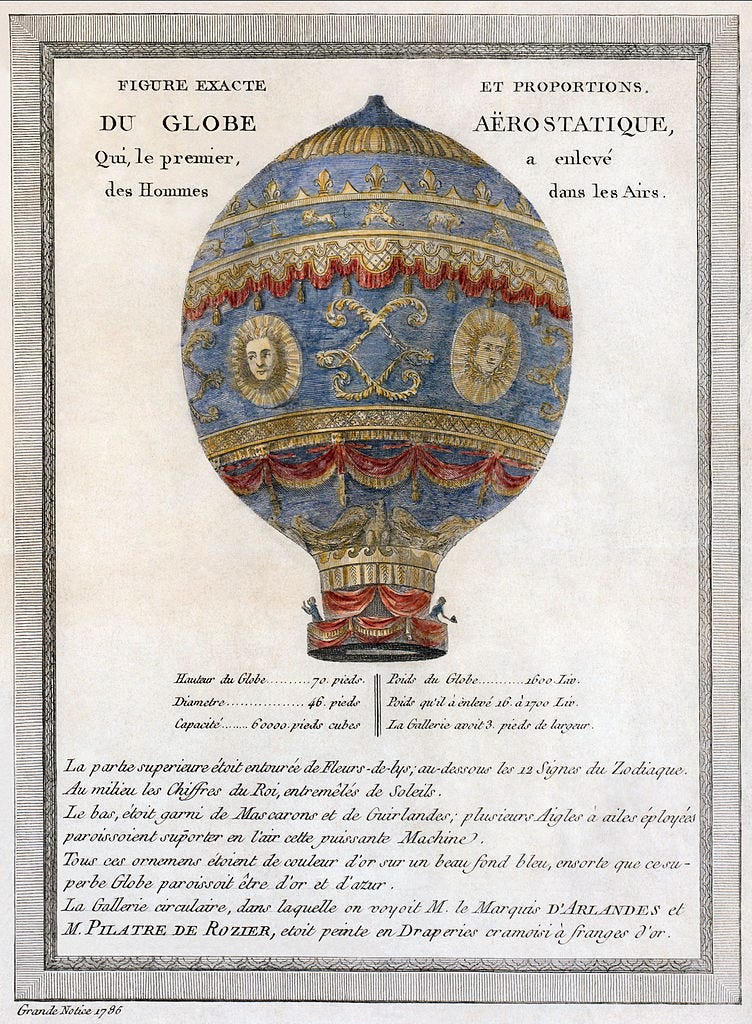

Across the Atlantic in France, advances in chemistry were conjuring new and ingenious flying apparatuses into being.1 France’s own revolutionary days were still a decade away when the first successful hydrogen-powered balloon was launched from the Champs du Mars, right next to the future (about 100 years hence) site of the Eifel Tower in Paris.

The balloon, christened Le Globe by its creator, flew for about 45 minutes (and Benjamin Franklin, who was probably out whoring and carousing instead of working on the peace treaty, was one of the spectators). The experimental balloon landed 15 miles away in the suburb of Gonesse. It was then attacked and vanquished by a mob of frightened peasants wielding pitchforks and other weapons.

The deflated and defeated balloon was subsequently tied to a horse’s tail and dragged through the town, where it seems the balloon was subjected to further abuses. The incident is similarly commemorated in a French textile sold at the time.2

As The Smithsonian’s Senior Curator of Aeronautics, Dr. Tom Crouch, notes, “[t]he sad demise of the world's first gas balloon led court officials to order an edict read in parish churches across France assuring the people that a craft such as this descending from the sky was a balloon, not a supernatural being.”3

II. High on Phlogiston

The invention of ballooning can be a bit confusing, as there were competing methods and launches occurring throughout second half of 1783. These balloon pioneers were likewise confused about how or why their balloons worked (owing to their reliance on the now-archaic theory of phlogiston, a kind of combustion potential inherent in objects that could be harnesses), but trial and error confirmed that the use of hydrogen or heated/expanded air would reliably induce ascension. So you get two competing camps (Charles and Montgolfier) using the two methods, and you end up with a mix of “firsts” between the two camps.

The balloon killed by peasants in August, 1783 was the work of Jacques Charles. He rushed to make his own balloon (selling subscriptions to help make a large volume of hydrogen for a demonstration on a date to be determined) after he heard about the Montgolfier Brothers (who were from a successful, multi-generational paper making family) working on a balloon of their own (which was successfully demonstrated in June, 1783 with a tethered flight). The Montgolfier’s apparatus then received interest from Louis XVI and a demonstration flight with animals succeeded (a sheep, duck and rooster returned unscathed in September, 1783), followed by a manned, untethered flight, the world’s first (November, 1783). Charles then followed with a manned, untethered, hydrogen-powered flight a month later.

III. Fashionable Elements

Watching men ascend into the heavens in balloons had a widely-documented effect of wonderment and euphoria on the events’ spectators. As Crouch recounts for the Smithsonian:

"It is impossible to describe that moment:" wrote one observer of a balloon launch, "the women in tears, the common people raising their hands to the sky in deep silence; the passengers leaning out of the gallery, waving and crying out in joy… the feeling of fright gives way to wonder." One group of spectators greeted a party of returning aeronauts with the question: "Are you men or Gods?" In an age when human beings could fly, what other wonders might the future hold?

For the December, 1783 balloon demonstration in Paris, it is reported that 400,000 people turned out (that’s fully half of the city’s residents). Even for those not fortunate enough to buy a ticket to launch demonstrations (or steal a view by climbing adjoining structures), balloon mania (ballomanie) would sweep France for the next two years.

During the height of the ballooning craze, few consumer ventures were spared from a speculative association with ballooning, no matter how tenuous. The sheer volume of balloon related bric-a-brac that has survived to the present from this period is one indication of how widespread the production of balloon-themed consumer goods had become (picture frames, chairs, candy containers, jewelry, door knobs, and so on). Some enterprising engravers would produce artwork commemorating a specific balloon launch before the flight took place (and taking no account of whether the balloon ended up crashing, failed to launch, etc.).4

Declaring normal consumer goods in the style “au ballon” had the effect of increasing sales (plates, fans, the textiles showcased above, etc.).5 It was the 18th century version of “put a bird on it.” The first toy balloons, powered by hydrogen, appeared for sale on the streets of Paris two weeks after the September, 1783 flight. French authorities had to subsequently ban the practice of making bootleg hydrogen in the home (a process involving dumping “oil of vitriol” (sulfuric acid) onto iron), given the inherent dangers of combustion.

Some of the balloon merchandise also had stupid sayings on it, like “adieu.” Still others satirized the movement by pairing balloon images with the slogan “Man’s greatest folly.” People also needlessly divided themselves among the competing balloonist camps, with those favoring the hydrogen-powered balloon (the charlière) engaging in shouting matches with those who favored the hot air-powered balloon (the montgolfiere).

In this excellent article Inflationary Models in Cabinet magazine, Sasha Archibald concludes that balloon mania receded in France when curvilinear Rococo styles were replaced by Neo-classicism (and as prophecy for 2003, offers up a nice image of Marie Antoinette as the original Goop woman, “let them eat collagen”):

The balloon motif, however, was short-lived. These fanciful styles were to be the last gasps of rococo; in a few years, fashion completely gave way to neo-classicism, inspired by idyllic rural scenes and epitomized in Marie Antoinette’s empire-waisted white muslin gowns, natural curls, and flat gold sandals.

Ballooning, however, continued its history of mishaps.

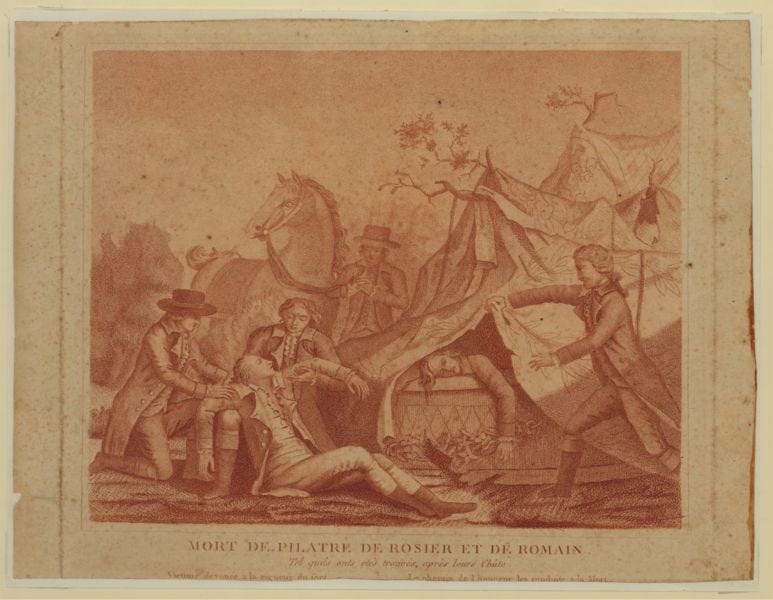

Ballooning does indeed have its history of mishaps, as the new flight technologies took some time to perfect (I was surprised to learn that as of the time of writing, 8 people have died in hot air balloon accidents thus far in 2024!). Rozier, one of the first aeronauts to fly in the Montgolfier device, achieved the dubious record of “first aviation disaster” two years later in 1885 when he attempted to combine the Charles and Montgolfier methods (essentially seeking to use both hydrogen and oxygen for his flight, resulting in the fiery destruction of his balloon thirty-three minutes into his attempt to cross the English Channel).

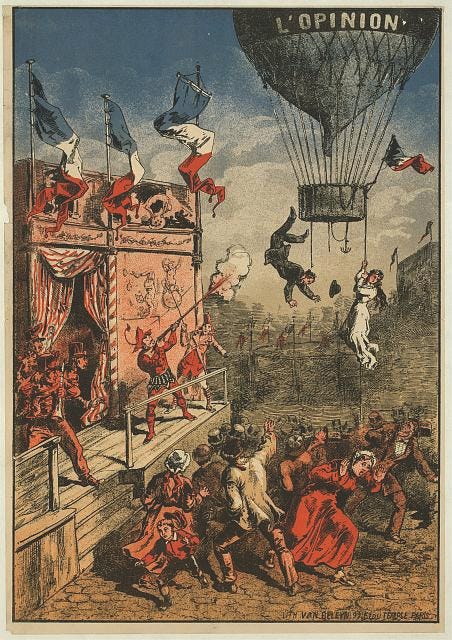

The deaths by fire and falling are obvious, but ballooning has less obvious cases of collateral damage (riots and other mayhem).6 And then there’s Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, a tax collector and hobbyist chemist whose experiments in pre-Revolutionary France helped replace the archaic phlogiston theory of gases and combustion with the discoveries that oxygen (formerly, phlogiston, or “inflammable air”) and hydrogen (formerly, “dephlogisticated air”) can be derived from water.7

Lavoisier’s tax collections work for Louis XVI made him a natural student of mass conservation (and he excelled at the obsessive weighing and measuring pre- and post- chemical reactions that allowed him to deduce the nature of these reactions).8 As Lavoisier mused, “[t]he ledger must balance; what goes in must come out; there must be no loss in either an accountant’s books or in a chemist’s laboratory.”

But in matters social there would be imbalance. Lavoisier was arrested alongside 27 other tax farmers on November 24, 1793 during the Reign of Terror. He was guillotined alongside his co-defendants six months later on May 8, 1794. Lavoisier’s contemporary, Joseph-Louis Lagrange, himself famous for work on the Three Body Problem and helping to develop the metric system, lamented: “[I]t took only a moment to cause this head to fall and a hundred years will not suffice to produce its like.”

The man who discovered the explanatory framework for the actual chemistry of hot air ballooning would lose his head on account (pun intended) of his day job. In being convicted and sentenced to die by his delirious new country, Lavoisier joked that at least he would die young and therefore “die in good health.”

Though hot air ballooning is mostly diminished to meteorological uses and hobby enthusiasts today, in one sense it helped give us the periodic table.

IV. Woodman, Meet Woodshed: Soul Flights of the Nazca

The modern-day Federal Aviation Administration manual on ballooning (which has some choice comedic bits we’ll save for a subsequent entry on this subject), mentions this about the history of ballooning:

It’s a throwaway line from the FAA manual, but this reference to the Nazcas of Peru (of Nazca Lines fame) possibly being balloonists stood out to me, and it now lets us conclude on something more interesting than European ballooning.

![The Astronaut (el astronauta)[68][66] The Astronaut (el astronauta)[68][66]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!sWA2!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1a3d9ddd-4985-4dad-ad2b-6da8389ea3a3_1280x1747.jpeg)

The Nazca Lines are sometimes brought up when you want to have fun with the Ancient Aliens branch of junk science.

The talking point is that such large format drawings could only really be seen (or made?) from the air. Erich Von Däniken also speculated, without any evidence, in Chariots of the Gods? that the pictoglyphs were instructions by and for aliens to land in the deserts of Peru.9

A less ridiculous, but equally debunked claim was then taken up by Jim Woodman in his 1977 book, Nazca: Journey to the Sun. Woodman’s hypothesis is that the Nazca possessed hot air balloon technology (and again, this reference has somehow found its way into the present-day FAA manual on hot air balloon operation). Woodman had this idea when he flew over the Nazca Lines and insisted that someone must have been able to fly to direct their creation.

Enter the website In the Hall of Ma’at, whose purpose is to weigh evidence against claims made by alternative historians.

In a delightful analysis by Katherine Reece from 2005 (Grounding the Nazca Balloon), we are presented with a simple refutation:

It is incorrect to say that the lines can not be seen from the ground. They are visible from atop the surrounding foothills. The credit for the discovery of the lines goes to Peruvian archaeologist Toribio Mejia Xesspe who spotted them when hiking through the foothills in 1927.

We’ve since found more Nazca drawings (and precursor drawings from the Paracu that influenced the Nazca) with the help of drones and artificial intelligence pattern recognition. These new drawings especially confirm the use of the drawings as landmarks that pedestrians could see while walking the desert (and the forests that existed there, as climate change is always doing its thing).

Reece’s refutation could end there, but gratifyingly it does not.

Woodman next points to the high quality of Nazca weaving as being suitable for a hot air balloon envelope. Reece’s response:

With the assistance of a local grave robber, Woodman plundered through the Nazca burial grounds gathering samples of textiles. He had these textiles analyzed and found that the weave is extremely tight and the thread count very high. He marveled that modern textiles do not come close to such high quality. Had Woodman searched the academic literature rather than plundering through ancient graves, he could have found this same information.

Woodman also claims that Nazca pottery has drawings of hot air balloons and kites. Reece would like us all to know that these pottery depictions are actually just beans:

We’ll mostly skip Woodman’s next claims about sending deceased aloft on balloons to reach the sun, as Reece reminds us that nobody would launch their ancestor burial balloon to watch the prevailing winds bash their loved one into a mountain.

Finally, Woodman refers to an Inca legend where someone utilizes flight to visit a neighboring city. Reece’s exasperated explanation that hundreds of years separate the Nazca and the Inca pales in comparison to this part:

Shamanism exists in many cultures worldwide both ancient and modern, one of the most common aspects of shamanism is magical flight. Under the influence of hallucinogenic plants shamans often have an out of body experience or “soul flight.” These flights can take place over both familiar and unfamiliar landscapes. This feeling of flight under the influence of a hallucinogenic is not limited to shamans, the majority of people who have ingested these plants have also experienced “flight.”

[…]

The shaman Antarqui having flown “by his arts” is a much more plausible explanation and has more supporting evidence in the Andean cultural context of “soul flight,” rather than the modern concept of a hot-air smoke balloon.

“Soul flight” and the hallucinogenic effects of these two plants can also explain the images of “flying men” that Woodman describes on Nasca pottery and textiles. Once again Woodman failed to supply any images of these “flying men.” These are however rather famous images and I am familiar with them. It would be more accurate to say that these images depict a hybrid combination of man and feline that flies, often, with the aid of wings. As far back as the Chavin culture in 1,000 BC there are images of supernatural beings, part man and part feline holding a San Pedro cactus, and South American shamans still today believe they can transform themselves into a jaguar or other type of feline by ingesting the cactus.

Hot air balloons are interesting. I am not sure they are more interesting than this notion of cactus-induced Soul Flight.

The Chavín culture that produced these Jaguar-Man images predates the Nazca by a thousand years, but there is some cultural continuity and Chavín works and motifs influenced them (some researchers think the Chavín created a jaguar cult that went on to experience very successful memetic spread throughout the continent). Below is one of the ceremonial carvings referred to by Reece, depicting a man-jaguar hybrid holding a San Pedro cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi). This cactus contains considerable amounts of mescaline and can be boiled to produce hallucinogenic teas (and unlike peyote, has a faster growth habit). There’s some evidence that Chavín stability and social control was maintained through a priest class communing through regular use of psychedelics (or possibly giving the psychedelics to their congregation). Some sources I’ve run across also maintain that warriors and battles are notably absent from Chavín art.10 I don’t know if that’s true, but if you have a Jaguar-Man who is tripping across the astral plane and has snakes for hair, what would you need warriors for?

For a last bit of context, I’ll rely on the writing of Sergey Baranov, who is active in the San Pedro cactus healing community:

Another central image of Chavin culture is what is known as Huachumero, an anthropomorphic figure, the Jaguar Man, who is holding a Huachuma cactus in his hand. You can see the original carving in the small circular plaza which was only accessible to the designated shamans. El Huachumero is not a diety but a medicine man who transformed himself through the huachuma cactus.

No writing has survived, so we don’t know what the Chavín called their Jaguar-Man (and the Chavín themselves are named after their ruined temple complex). With balloons faded into obscurity only 250 years after being a potent craze, I’ll place my money on the Jaguar-Man, still going strong 3,000 years later.

It made all the balloon research worth the trip.

//

As for the Nazca hot air balloon, I’ll leave the final word with the highly accomplished hot air balloon consultant that Jim Woodman hired to help make his Nazca ballon fly. Here’s legendary aviator Julian Nott:

When Jim Woodman approached me with his idea that the people who created the Nazca lines could have seen them from hot air balloons I was intrigued but skeptical. Yet we successfully flew in a balloon that could have been built by the Nazca people a thousand years ago. And while I do not see any evidence that the Nazca civilization did fly, it is beyond any doubt that they could have. And so could the ancient Egyptians, the Romans, the Vikings, any civilization. With just a loom and fire you can fly! This raises intriguing questions about the development of science and, most of all, the intellectual courage to dare to fly, to dare to invade the territory of the Angels.

Any civilization can fly, with a loom and fire (or a cactus).

Ben Franklin, John Jay and John Adams observed the launch of many balloons while stationed in France and working on the treaty to officially end the Revolutionary War. Washington was likewise impressed with hot air balloons, writing to a friend in 1784: “I have only news paper accts. of Air Balloons, to which I do not what credence to give. The tales related of them are marvelous, and lead us to expect that our friends at Paris, in a little time, will come flying thro’ the air, instead of ploughing the ocean to get to America.” Many of the founders would go on to witness hot air balloon launches when they jumped the Atlantic to the United States, which we will not discuss here because it is boring.

The curious history of French news-textiles is described by the Cooper Hewitt Gallery (which is housed in the New York Carnegie Mansion): “Textile producers realized that depicting contemporary events on fabrics would result in greater sales because the fabrics would appeal to a wider audience and, in addition, serve a patriotic purpose by celebrating French achievements. Le Ballon de Gonesse, produced by the Oberkampf factory in Jouy, depicts three balloon scenes from events that took place in 1783…[a]lthough these fabrics had the widest appeal, it is not surprising they also went out of fashion quite quickly and became unsellable, especially if commemorating political events, as the public’s focus shifted to the most recent news.” In this, we can see the beginnings of fast fashion and the even faster news cycle.

I searched, but could not find a copy of this edict. I think its contents would be supremely interesting. How might one try to reassure people about the new phenomenon of powered flight?

In this, we see a curious precursor to the American Super Bowl habit of printing a bunch of dumb hats and shirts for both contending teams (a few thousand items for each team), though only one will actually win (to take advantage of victory-elated purchasers). The losing team’s “surplus goods” are seemingly donated overseas, and I lack the research stamina to find out whether any of these items end up in the Atacama.

For much of this detail about French balloon mania, I’m indebted to the excellent long form essay The Balloon Era, by Rénald Fortier, Curator of Aviation History at the Canada Aviation Museum.

Riots at balloon exhibitions became a known risk to French authorities (around 60% of balloon launches ended in failure as increasingly lay people took up the sport and excitement outstripped competence, resulting in hostile crowds). One balloon launch in Bordeaux caused a riot that killed 4 people (2 in the melee, 2 more hanged as a result, and 7 incarcerated). By April, 1874, the city of Lyon had banned hot air balloon flights, as the vehicles had a tendency to combust over equally combustible rooftops, especially when fireworks were involved (Moscow was ahead of the curve for once as Catherine the Great banned such flights in Russia the same year).

For this account of Lavoisier’s work, I’m indebted to James L. Marshall’s (Professor Emeritus University of North Texas) article True Elements — Lavoisier and Phlogiston. It should also be noted that Lavoisier’s work built (without citations or credit) on the work of Cavendish (isolating hydrogen) and Joseph Priestly (isolating Oxygen). Lavoisier’s work was nonetheless revolutionary for demonstrating water was not an element, but a combination of two more fundamental elements. He went on to identify 31 elements in a 1789 treatise on the subject.

It also made him a lot of enemies, as his institution involved building a wall around Paris in order to collect more taxes on behalf of the crown.

Carl Sagan’s review of Chariots of the Gods? is too good not to include: “That writing as careless as von Däniken's, whose principal thesis is that our ancestors were dummies, should be so popular is a sober commentary on the credulousness and despair of our times. I also hope for the continuing popularity of books like Chariots of the Gods? in high school and college logic courses, as object lessons in sloppy thinking. I know of no recent books so riddled with logical and factual errors as the works of von Däniken.”

The temple complex where this carving was found was started in 1200 BCE (there are older ones in the Supe Valley dating to 2900 BCE), and there’s evidence of the Chavín culture experiencing destabilization and decline between 500 and 300 BCE. Since the climate preserves bones so well, a recent study was able to document this period of decline and a “bio-archaeology of violence” with stunning clarity (of 67 skeletons analyzed, 80% had traumatic, mortal injuries).