Sublime Prosaic completionists may have been tempted into thinking I’d forgotten about my sports and leisure vertical, The Sporting Life. Assuredly, I did not. This one has drinking, horse racing, gambling, self-delusion, frolic and detour, all in equal proportion.

Conceptually, you can just pretend this one is the last segment of an episode of This American Life. In Ira Glass’ voice: “Act Three, the Men Who Live in Hotels.”

//

I. Lounge Chair

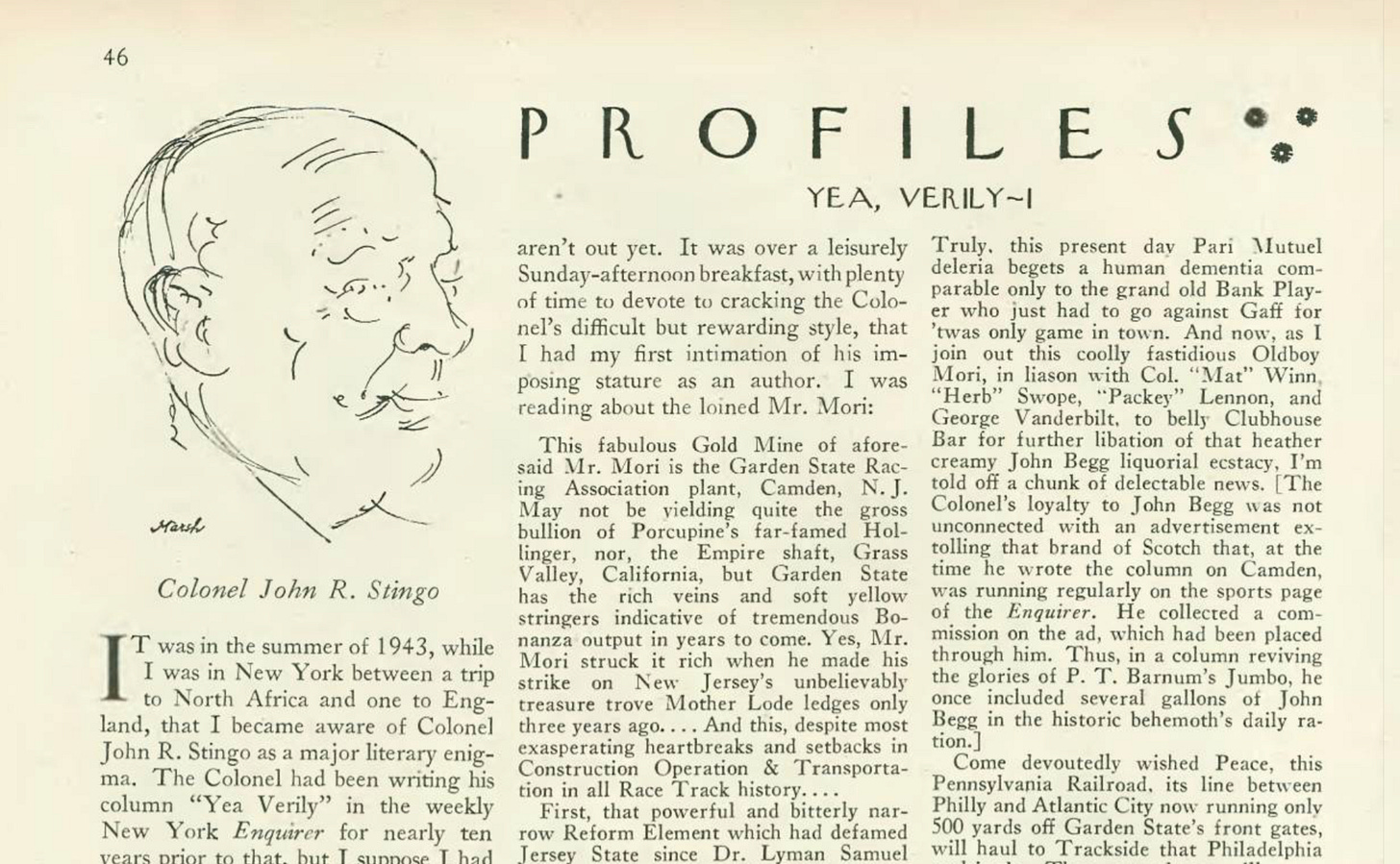

My wife recently forwarded a story to me from The New Yorker’s archives. As you can glean from the preview below, she knew this would be squarely in my areas of interest.

The article is a profile of Irving V. Link, described by the author Adam Gopnik as:

…one part Meyer Wolfshiem, one part Colonel Stingo, and eight parts everything your grandfather in Fort Lauderdale would dream of being if only he could get loose from your grandmother. He is certainly the best-dressed eighty-seven-year-old in America. He is slim, has beautiful, almost silver-white hair, a dashing white mustache, which recalls those of the rakish leading men of the forties—Cesar Romero or Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.—and a wardrobe that extends into new vistas of rococo elegance every time you see him.

I was completely enthralled by an account of a man who inhabited such a thoroughly self-constructed world, but also alarmed about the impending closure and remodel of The Beverly Hills Hotel. A few friends that were also reading the article were experiencing the same confusion (and references to fax machines and other archaic details were slipping by unnoticed), until someone set us right by pointing out the article is from three decades ago. First there was embarrassment about my level of reading comprehension (at a minimum, the date is printed right at the top). And then there was that feeling of saudade that came over me in realizing I was reading about a person and a world that was already long vanished.1

Aside from laying by a pool and playing gin rummy all day striking me as a laudable enterprise (Link had a wife and two children, about which little is written in the article, but he was otherwise at the pool for about fifteen thousand days of his life), the casual and passing reference above to “Colonel Stingo” jumped out at me. The writer assumed his readers in 1993 would just know who that is. I was completely unaware of this individual, and he has no Wikipedia page. In searching out this colonel,2 I was taken down the kind of rabbit hole I seldom regret.

II. Notable Prose

The writer of the Irving Link profile trusted the readership of The New Yorker to know all about Col. Stingo. This gambler and sportswriter (and permanent hotel resident) was catapulted to a very similar kind of literary stardom by A.J. Liebling3 in the same publication forty years prior.

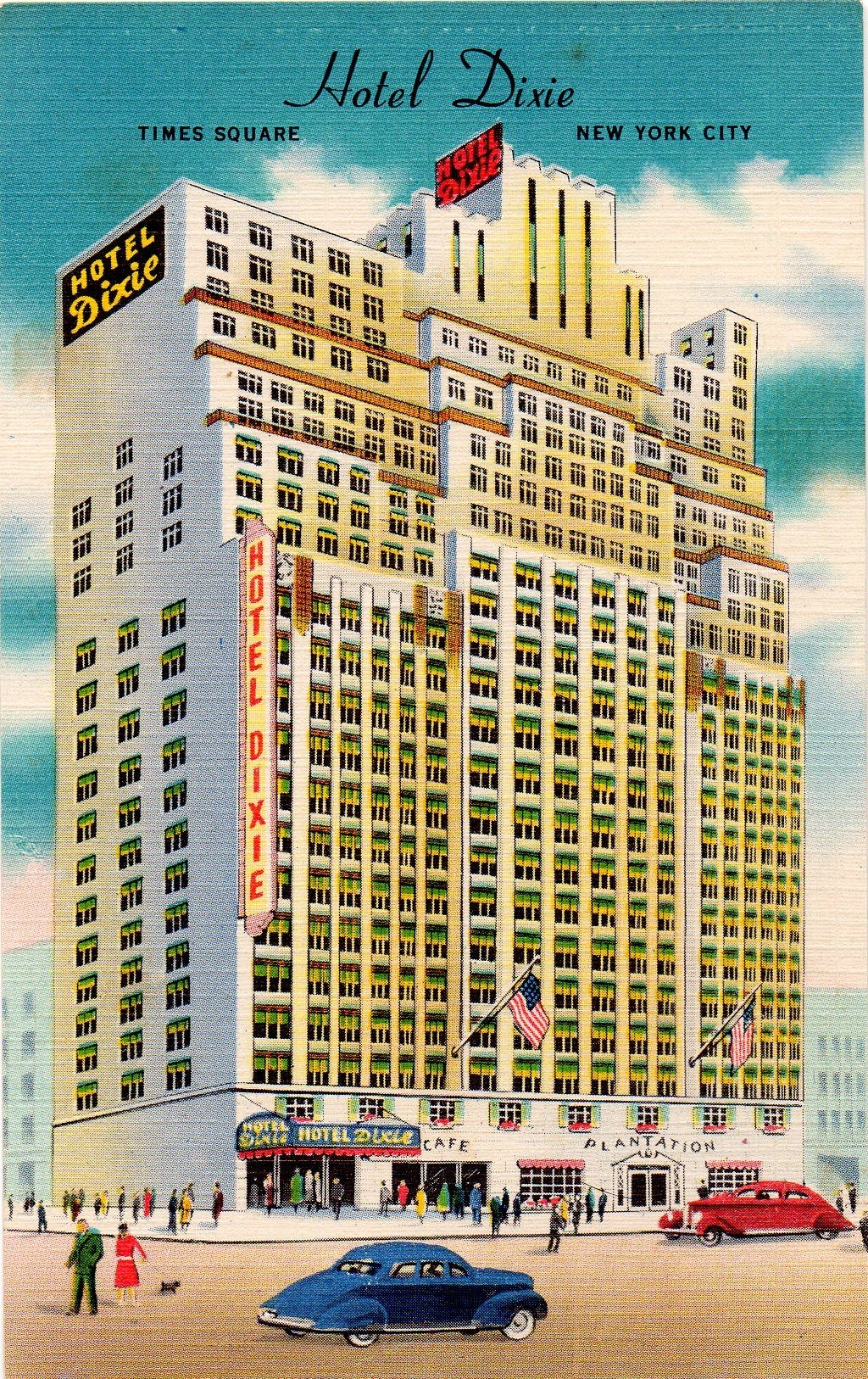

Liebling first introduced Colonel John R. Stingo to readers in a series of columns in 1952.4 Col. Stingo (real name James Aloysius MacDonald) was a sportswriter and man about town in the Times Square scene, who lived in the Dixie Hotel and seemed to get by through a combination of writing, gambling, writing about gambling, and various other schemes.

Later descriptions of their relationship often state Liebling was the Boswell to Stingo’s Johnson. If you’re like me, that is also not a helpful reference and a small digression is needed before we can move forward. James Boswell, 9th Laird of Auchinleckis, is a guy who wrote a biography about Samuel Johnson, who is perhaps best (sadly) remembered 300 years later as a guy from this meme portrait:

Boswell’s biography of Johnson, replete with personal details and anecdotes, is remembered, if at all, mostly by literary types as being the greatest (or first modern?) biography in the Enligh language. So Liebling’s writings about Stingo are characterized in the same way. The two would get together and basically drink all day and Liebling would dutifully record, and sometimes interrogate, Stingo’s reminiscences. Liebling’s prose takes a backseat in these encounters and Stingo’s unique, damascened style takes over, or as a review in The Washington Post bemoaned in 1989, “the result is that there is too much Stingo and too little Liebling, and that is a mistake.”

I haven’t finished this book, which feels strange to admit since I’m here writing about it. While I’m not at liberty to finish any book in the course of a week, no matter how slender or engrossing, I’ll say that the book is strong out of the gate (and may or may not be an improvement on how the three part profile was originally presented).

First, Stingo’s early career as a rainmaker takes us to some of the most forlorn parts of California. In places like McKittrick, which is known today only from the “Button Willow-McKittrick” sign off the 5 freeway as one breezes past Bakersfield. Wikipedia forlornly notes that “[t]he population was 115 at the 2010 census, down from 160 at the 2000 census.” If that trending decline held, we can assume there’s about 50 people there today.

Somewhere around this area, Col. Stingo worked for Professor Joseph Canfield Hatfield's Rain Precipitation Corporation, which would fire volleys of gatling gun rounds at hillsides (in a sincerely held but mistaken belief about the the ability for percussive action to cause rain).

Stingo also wrote about horse racing and turf matters in New Orleans (until the sport and related betting were banned for a time because there was just too much of it going on at all hours of the day). He next went on to become involved in something called The Great American Hog Syndicate, a scheme that allowed small investors to own fractional shares of a pig and participate in the pork sales/futures markets in the run up to The Great War. He claims to have made $500,000 from the scheme.

Liebling was immediately drawn to Stingo’s writing on the turf and horse racing worlds (part of his weekly Yea, Verily column for the Enquirer) when he first encountered it in the summer of 1943. The article that grabbed Liebling began with Stingo’s description of Eugene V. Mori, Sr. (erroneously referred to by Stingo and/or Liebling in recollections as Eugene Tomasso Mori), a new 53% owner of a racetrack in Camden, New Jersey:

Loined in nonchalant Palm Beach kalsomine white duck and tabbing his program with a stubby lead pencil, he is watching handy field of sprinters trot postward in Fleetwing Handicap, 3 Y.O. & U. 6 furlongs, here this afternoon.

Liebling subsequently championed Stingo as “the writer of what I would consider the most distinguished prose in the metropolis…” It’s replete with a very specific kind of horse racing jargon, the kind you would only see now in a set of handicapper’s notes you buy on the side of your racing program at Santa Anita.

If Stingo’s style was hard to follow in the heyday of racing (and it really can be exhausting), it’s entirely baffling in the 2020s. Here is Stingo describing his role in an “Honest Rainmaking” scheme with Professor George Ambrosius Immanuel Morrison Sykes D.D. (Zoroastrian), who had been summoned to a New York racetrack from Burbank, California (to try to prevent rain for the benefit of an ongoing horse race, rather than cause it):

“So I was in like Flynn, for 45 percent of the whole deal, which like a promising but untried mining claim we did not yet know the full value of, yet it bore a Bonanza aspect.”

Meandering sentences and strange metaphors are Stingo’s stock and trade. As Liebling put it, “[h]is sentences soar like laminated boomerangs, luring the reader’s eye until they swoop and dart across the mind like bright-eyed hummingbirds, for a clean strike every time.”

Stingo’s blustery, “long rider” way of life and the frame of reference that accompanied it are beyond extinguished. There’s a constant invitation (or temptation) to the reader to put down his writing and go try to figure out who/what/where he is talking about, and more importantly, if any of it could possibly be true.

III. The Yellowed Back Issues

Another unexpected delight in going back to read Liebling’s three original columns about Stingo in The New Yorker Archive is the ads! And I mean the publication is full. of. ads.

The ads are glorious. We are returned to a world where one can “LEARN PIANO TUNING BY MAIL” and it seems like a good prospect. A oddly-shaped woven basket that holds a single bottle of wine is pitched as “the gift for the person who has everything.” Looking for golf in Ponte Vedra, Florida? They’ve got you covered. There’s an address where you can write to inquire further, or you can contact your local travel agent.

In an odd bit of advertising serendipity, Colonel John R. Stingo has been described in retrospect as a “Runyonesque” character. This moniker is borrowed from the writing of Damon Runyon, who helped popularize the Times Square world of mobsters, hustlers and other lowlifes with colorful nicknames. What are we to make then of an ad for Runyon’s play, Guys and Dolls, being run opposite a column about Stingo?

If Liebling’s interest in Stingo ever started as a joke (something like Picasso’s dinner for Henri Rousseau), that’s not apparent from how he has written up their dialogues. The admiration seems sincere. The forward to The Honest Rainmaker is written by Garrison Keillor and Mark Singer. I’ll trust their opinion when they say the following:

“When he bluntly proclaimed Colonel Stingo ‘my favorite writer,’ no more than the usual irony was intended. What he really meant was that Colonel Stingo was his second favorite writer. He was Liebling’s Liebling.”

How could two vibrant men fade so entirely into the background of American cultural memory? Maybe it has to do with the decline of newspapers and the diminishment of the writer as celebrity in general, but the 1989 review of Liebling’s book in The Washington Post maybe explains it best (emphasis added):

A.J. Liebling was an uncommonly gifted journalist who wrote for the New Yorker when that magazine was in its prime and who dealt in matters now rarely encountered in its pages: food and drink consumed to exuberant excess, newspaper barons and Southern politicians, pugilists and gamblers, con men and marks. His prose could be crystalline or baroque according to the circumstances, as could his mood be waspish or ebullient; but he was always a master reporter, a man who loved to go forth into the world and ferret out its surprises. In all he was a wonder, and innumerable readers still miss him more than a quarter-century after his lamentably early death. But journalists write to the moment, even the best of them, and once they stop writing they gradually fade away into unopened files and yellowed back issues…

We’re left to contemplate a vanished world, one populated heroically by equally vanished lives.

IV. In Media’s Rest

Outside of Liebling’s mentions of them, the people and events spoken of by Col. Stingo do not exist on the internet as far as I can tell. If Stingo’s remembrances were not verifiable when Liebling receives them in the 1950’s, they are even less so today. Reading these conversations is escapism to a deeply analog world. As Stingo himself would tell Liebling when pressed too hard for details (or confronted by Liebling with history’s refutation of any Stingo’s claims, as in the case of a sheriff who would routinely fire rounds at a newspaper editor in his office in New Orleans), Stingo would state “the memory grows furtive…”

Liebling was eager to defend Stingo’s embroidered narratives, observing that where Stingo departs from history, he always “improves it.” All this jollity eventually came to an end, of course. Despite his heavy drinking (he would often go out and get “stiff as a board”), Stingo outlived his tablemate Liebling, who died a year prior in 1963. As Keilor and Springer put it best: Stingo “outlived his Boswell, though of course it is Liebling who survives.”

Returning to the world of poolside Los Angeles, Irving Link’s obituary does not mention his brush with fame in The New Yorker as the world’s most accomplished member of homo littoralis, but does commemorate him thusly, which seems just as well: “Irving's remarkable presence, astonishing good looks and ability to relate to any type of person in a kind and gentle fashion made him a hero to everyone who knew him.” He died in 2007 at the age of 101. The trick to longevity may have been to avoid the racetrack and spend more time in the cabana.

//

Internet Bycatch

An especially good haul of internet stuff this week—very little to throw back.

I recently followed Yann Vasnier on Instagram, as he created my favorite summer fragrance: Tom Ford’s Costa Azzurra (old version please, no Estée Lauder reformulation/gold bottle for me, I just can’t trust it). I realize my enduring love of a Tom Ford fragrance might be outing myself as a basic bastard, but that’s fine.

So I read the NYT profile of the “Mad Perfumer of Parma,” Hilde Soliani, with great interest. It’s a must read. It convinced me I’m never going to know anything about fragrance, but I’m happy to see someone pursuing their own vision without compromise. From the article:

Her packaging is unpolished, the range of her scents is feral and her website’s design screams “credit-card fraud risk.” Most important, she is unconcerned with coherence. Coherence is for brands, not artists.

Also:

She remains still when conversing except for her El Greco hands, which palpate and prod the air, and her head, which undulates and swivels. When moving through a crowd of darting and preening Italians, her presence is anomalous — a sea anemone amid parrotfish. She appreciates people with assertive taste, a cultivated palate and a touch of insanity.

Here is one of her fragrances that intrigues me. Purezza, or the small of laundry hanging on a hot summer day:

Esquire is out and about with designer Paul Smith in this piece, discussing his career and lesser known love of classical painters. He has one exchange that perfectly encapsulates what I like about him as a designer (small, unexpected details):

Q. Has your personal style changed much from the inception of your brand to where you sit today?

A. Not really changed. It's always been... It's a very overused phrase, but it's classic with a twist. So what it means is that, generally speaking, the clothes are very wearable, but they've normally got a little secret or a little unusual point, or then there's nothing unusual about the clothes, but it's the way you put them together. It's always been just slightly contradictory or to do with kitsch and beautiful, or rough and smooth, or workwear with posh, or playing with contradictions.

An interesting piece in The New Yorker that helps us properly see through the veneer of AI in its current state. Our chatbots are a fascinating piece of human achievement, but also prone to the same biases that made us think Furbies were alive/greater than the sum of their parts. ChatGPT is not much beyond Paro as of now. It’s further notable to me for echoing some of my themes from last month’s Passing (Alpha) Go, a retrospective on mechanical minds (real and simulated), and how AI today is something like a toy, but on track to become something more God-like.

Blancpain using some of their watch money to sponsor underwater expeditions has always felt like money well spent. Here they are looking for coelacanths in Indonesia’s mesophotic reefs. A good use of 12 minutes.

This bitter sensation of past tense has started to become familiar to me. You learn about something amazing, only to realize you missed the height of that thing being in the world. It’s looking forward to someone’s birthday party only to find out you’ve been invited to a wake instead.

If you want to know more about when one should capitalize “Colonel,” I can only say that I don’t know, but I have a court case for you. It turns out The Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels (HOKC) went after the Kentucky Colonels International (KCI) for trademark infringement, dilution, cybersquatting, and defamation in civil court in 2020. The 2,000 page lawsuit was dismissed and a preliminary injunction was granted. Here’s the summary from the American Colonels Network, although the same summary states “[e]ven the Court was uneducated about the idea of the Kentucky colonel and was confused”:

Then on August 13, 2020, the Honorable Order [HOKC] was granted a Preliminary Injunction against the defense [KCI] for using the generic term "Kentucky Colonels" as a component of its descriptive trade name or as a descriptive domain name until the case can be concluded to protect the Plaintiff and the public from potentially being confused about the subtle difference in English grammar that gave the HOKC a valid trademark. It was understood the difference between title case and normal case makes or breaks their trademark, using "Kentucky colonels" with a lowercase "c" refers to colonels as people and writing "Kentucky Colonels" with an uppercase "C" refers to the Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels (most of the time).

As serendipity would have it, The New Yorker has a retrospective on Liebling’s life and work out this very week, which can be helpful for the unfamiliar. Liebling’s profile of Colonel Stingo was notable enough to be mentioned in Liebling’s 1963 obituary in the New York Times (and it’s a packed one, considering we was a press correspondent during WWII and was at the landings at Normandy). In addition to horse racing, he was also enamored with the subjects of boxing, drinking and eating. From the NYT obituary: “Despite the considerable breadth of his published works, it is likely Mr. Liebling most enjoyed his role as a press gadfly. His favorite themes were the diminishing competition and consequent loss of enterprise caused by mergers and sales.” I don’t have any answers for the news business, but it feels like we could use some of that spirit today.

The forward to the book version of The Honest Rainmaker states Stingo first showed up in “Wayward Press” in 1947, although I couldn’t locate that in the archives.