Garden Aisle on Sublime Prosaic is generally about gardening and plants. This week, it’s partially about my enduring fascination with things made out of endangered wood.

//

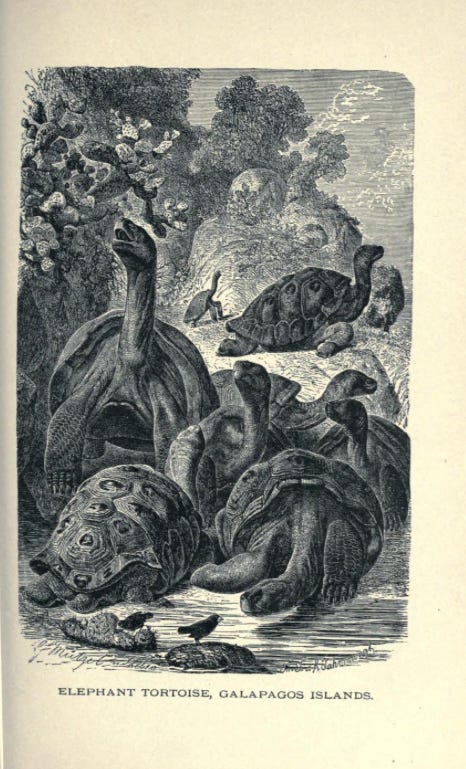

Sometimes the allure of an object is that you can’t really get it any more. I suppose Four Loko and quaaludes come to mind, but also the opportunity to eat Galapagos Tortoises.1

Growing up, I was fascinated that early Eames Lounges were originally made of (now) endangered Brazilian Rosewood.2

This fascination with rare (usually disappearing) and high end materials has stayed with me.3 And so I was thrilled to learn about a new wood in August when I was writing extensively on the history of the butaque. A reader with superlative powers of recollection will know that the Taíno peoples (original inhabitants of the Caribbean, largely but not completely erased by the ravages of First Contact) created duhos out of lignum vitae. But it turns out I had run into this material much earlier than August, 2023, but took little notice of it.

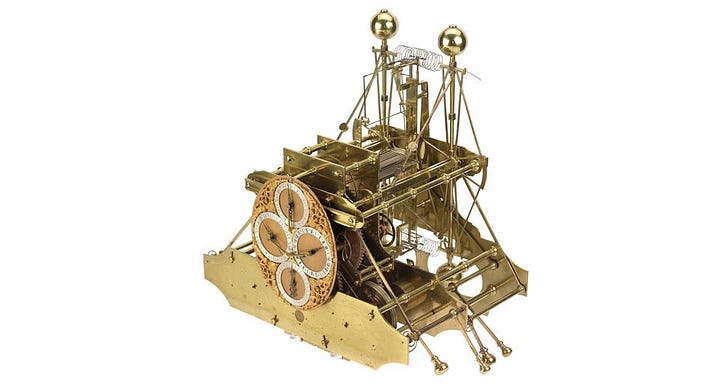

If you hang out with me long enough, I’m going to want to talk to you about Longitude. This book is a hall-of-famer in something a group of close friends has termed “The Dad Bookclub.”4 It defies an easy summary, but Longitude is the story of an incredibly gifted clockmaker who spent his life working on a solution for the problem of keeping track of where you are at sea. It was the mercantile/colonial era, so Harrison was pursuing a kind of 1700s X-Prize issued by England’s Parliament—the solution had national security and commercial implications for European colonial navies and chartered companies (the Dutch East India Company had 40 warships and an army of 10,000 individuals at its height). Harrison eventually produced a pocket watch-sized marvel: the H4.

Harrison’s timekeepers, as it turns out, use bearings made of lignum vitae (except for the H4, owing to its small size). Harrison’s clocks still run today, thanks in part to the meticulous care of specialists at the Royal Museums Grenwich, but also because the lignum vitae bearings are self-lubricating.

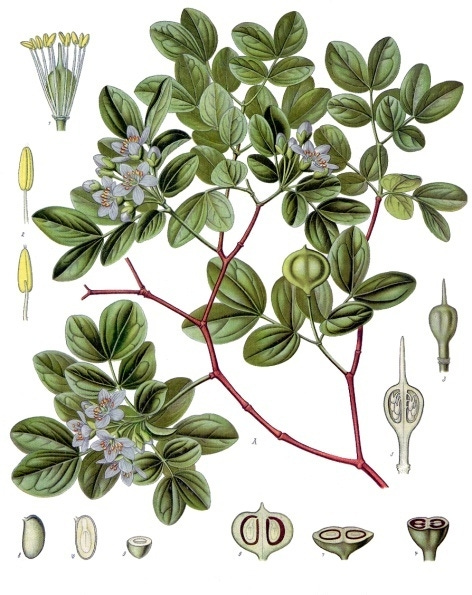

True lignum vitae comes from the guiacaum tree (the varieties sanctum and officinale), members of the caltrops family (a small family, but creosote is a relative), which had an original range in Florida, parts of the Caribbean, Mexico and Central America.

The Taíno peoples considered lignum vitae sacred and had many uses for the tree, including in medicines. Europeans then ran with the idea that guaiacum could help treat syphilis.5 The idea was subsequently dropped due to lack of efficacy, but some allusions to guaiacum as a cure-all linger on in its use in drinking vessels (see the curious connection to wassailing, below).

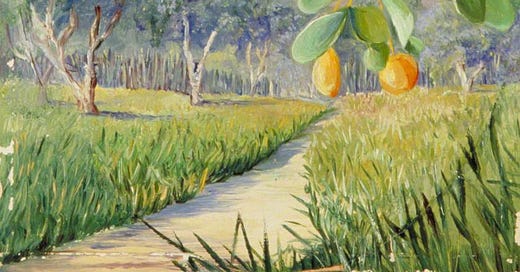

Guaiacum is an extremely slow-growing tree that can reach 30 to 40 feet in height, and the US Forest Service depressingly notes: “few people have seen plants of this size because it is not grown in the trade.” From its original range, there are a few remaining pockets of original hardwood hammock. One such place is in that magnet for all things weird, the Florida Keys. Lignumvitae Key has retained an original population of these trees, seemingly because shallow sand bars made the island difficult to approach in high draft European sailing vessels.6

The same properties that make lignum vitae useful also mean it is incredibly slow-growing (about 2 inches a year) and therefore prone to over harvesting.7 The wood is incredibly dense, making it an “ironwood” or one of the few woods that does not float (take your Catalina Island murder jokes elsewhere).

In terms of hardness (according to the Janka Hardness Test), Lignum Vitae is very high up on the list. Wikipedia and WoodDatabase.com don’t necessarily align in what woods on our planet are harder than Lignum Vitae (Wikipedia has it at number 2, WoodDatabase at number 5), but it’s hard enough to have military applications (propellor shafts, including on some of the first nuclear submarines, plus plenty of other components like replacement bearings for the current Indian Navy).

Probably easier to let someone from 1919 explain it:

A Brief History from: United States Naval Institute proceedings, Volume 45 P. 1929

Lignum Vitae, The Vital Wood.—The propeller shaft of every battleship, every destroyer, every transport, in fact, every large steamship, revolves in a wooden bearing at the stern end. Of all the thousands of woods in the world, true lignum-vitae, is the only one that has been found equal to this exacting service. The peculiar properties which so well fit lignum-vitae for the purpose are due to the arrangement of the fibers and the resin content of the sap cells. The fibers never run straight up and down the log, but weave back and forth in a serpentine manner that cross and crisscross like the corded fabric of an automobile tire. The result is a material of extreme tenacity and toughness. When the sap cells cease to function, their every nook and cranny become filled with resin which is about a third heavier than water. The result is a material which weights about 80 pounds per cubic foot.

—Engineering World, Oct. 1, 1919.

It turns out the shipping industry has a few specialty publications that still extol the virtues of lignum vitae. There are plenty of people who think about lignum vitae seriously, and not as historical minutae.

So this wood is (i) low yield and high value (making it endangered and expensive where you can legally obtain it), and (ii) tied up in an obscure way with various vanished economies of the colonial and mercantile eras (making it, at least to me, fascinating and worth collecting).

It turns out that other people like this tree enough to try growing it in places where it really shouldn’t do well—it can be a curious ornamental tree in Miami and a beautiful affront to geography in Rancho Mirage and other parts of the American Southwest. I wouldn’t mind trying to keep one alive should I come across the opportunity. To the extent the tree may not do as well in Los Angeles, I also have the option of buying my own lignum vitae objet — it turns out there’s plenty of them around. You can find lignum vitae objets in a variety of form factors: a microscope, bocce balls, bowling balls, police truncheons, cricket bats and of course punch bowls and loving cups for wassailing.

For plenty of people, I think this examination can seem like a lot of rhetoric about nothing, but this closer inspection of lignum vitae illustrates the aims of my Sublime Prosaic project quite well. To most, it might just be wood, but we all ought to know better.

I’m a custodian for a desert tortoise and I almost never feel the need to signpost when I’m in a satirical mode, but I have to clarify that this joke even makes me a little sad (and is in bad taste [pun intended {oh no, don’t do nested jokes in a footnote, look at how many bracket styles this required, reign it in SF}]). Still, it’s worth remembering that many species of these island tortoises were widely reported as being delicious. If you keep up with developments in the “possibly eating tortoises” space like I do, you already know there are plans for lab grown meat in the works, and that unfortunately someone has been eating them as recently as last year, despite their protected status.

My grandparents had a Plycraft replica of this lounge and ottoman in a supple cognac leather at their cabin in Pine Mountain, so my fascination with this lounge and ottoman started in the late 90’s. I wonder if the knock off’s veneers were Brazilian Rosewood as well? I’m also using “endangered” in a non-technical sense here. Here’s a guide from WoodDatabase.com if you want to sort out the overlapping international designations for when the wood in question is coming from an “endangered” or merely “threatened” tree.

I’m not into ivory so save those keyboard strokes if you’re concerned about that. Everyone has their own subjective level of tolerance for butchering/wearing sentient beings. I know a Texan who has a pair of much-loved, bespoke elephant skin boots. They are presumably legal, but I’ve always marveled at that choice. I’ll save the general subject of exotic leathers and the unreal promise of genetically engineered stingray shoes for future installments.

To qualify as an entrant into Dad Bookclub, the book should be non-fiction, about history, war or nautical feats (bonus for all 3) and somewhat esoteric. Werner Herzog’s excellent novel, Twilight World, qualifies. Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World and Greyhound are great film examples.

From the excellent NIH article on guiacaum: “Historical records state that 21 tons of guaiacum reached Seville between 1568 and 1608, while by the 18th century guaiacum imports disappeared from Spanish trade records.” Guaiacum has also made a modern medical comeback as an important component for early detection of colorectal cancer.

My thanks to Brad Bertelli of Keys Weekly for the background here.

Much like the overharvesting of silphium in the Mediterranean. A kind of giant fennel, silphium was delicious to cook with (we know this from millennia old cookbooks), a natural means of contraceptive (hence the very grounded fears that overconsumption caused its extinction), and perhaps has finally been rediscovered growing in the wild in Turkey recently.