You want hat facts? No, I didn’t think so either, but here we are.

This one started as a simple desire to talk about the forgotten history of beaver felt in making hats (and how hats have been forgotten as a kind of social technology in their own way). As it turns out, the entire history of hats is too important and interesting a subject to be jammed into an article about the planet’s second largest semi-aquatic rodent. I also felt this piece start to slip away from me the longer I read about the subject matter, so I felt compelled to get it out before I lost my grip on it entirely. This first installment functions as an introduction to a longer series about felt fur hats, focusing first on the natural history of the animal that supplies the materials.

Working title for the series: The Alchemy of the Milliners.

//

I. The Fate of Charisma-Challenged Species

When might the total eradication of a species be beneficial? Aside from some invasive varieties of mosquitos, I am hard pressed to think of an organism we are sure we could do without (even mosquitos are doubtless food for something). A billboard for the final season of Curb Your Enthusiasm in mid-city last week (of all things) put this on my mind.

I think the upshot of this imagery is less that Larry David’s character is an iceberg (or the snows of Kilimanjaro), but more so that he’s like a polar bear (forced to swim further in search of seals to eat on the dwindling sea ice).1 In the world of Larry David’s show, where people are openly hostile to him as a matter of course, it’s not hard to imagine a lot of people rooting for the disappearance of this particular kind of endling. Conservation in real life is full of stories like this—cute, inspiring or endearing animals rally human support and get saved. Non-charismatic organisms, even if fundamentally important to their ecosystems, receive only oblivion.2

The beaver, which we once hunted to scarcity on every continent where they could be found (and whose charisma remains very much in question), is an animal that has been given the chance to rebound. Shifting fashions helped save it from destruction, and now its resurgent populations are helping drive certain climactic effects.3

It’s a curious kind of revenge for the beavers. They’ve gone from dying en masse to make our hats to helping advance the meltwaters of our climate collapse. Humans, in abandoning felt fur hats, are now the charisma-challenged species. How did we get here and whom might we blame?

II. The Life (Semi-)Aquatic

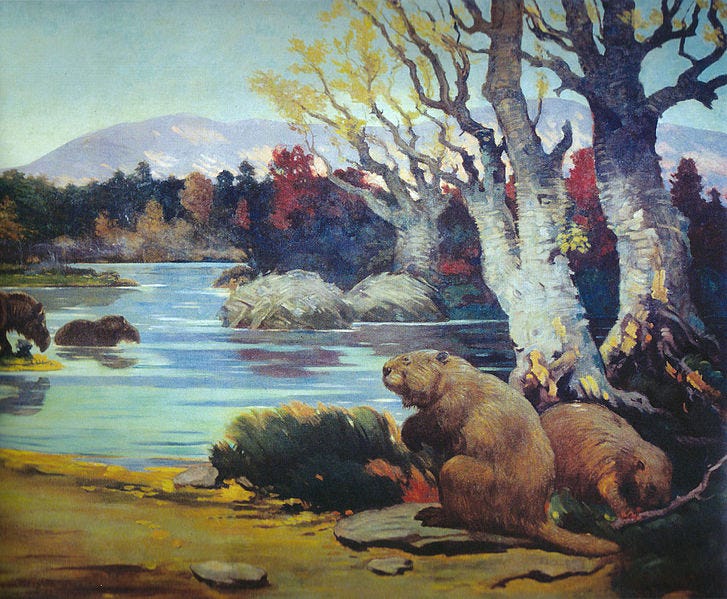

The Pleistocene had beavers the size of bears that roamed the United States. Their demise is a source of conjecture, but we either ate them to death or they were too lumbering to adapt to new temperatures and environs as the glaciers retreated (they also lacked the pond making and engineering skills of their smaller successors).4

Our smaller, modern beavers (Castor canadensis in the Americas and Castor Fiber in Eurasia) were also once widespread in the Northern hemisphere. Beavers are known for the irrepressible penchant to engineer their environments, damming up running water to create the ponds in which to build their lodges. They have been doing this to the temperate landscape and expanding/maintaining wetlands for at least 33 million years. Humans have been around for about half a percentage of that time, but we’ve more or less worn hats since we appeared on the scene.5

In Europe, beaver caps were associated with quality and utility since antiquity, with one early mention surviving in The Canterbury Tales (1387-1400). Then the Thirty Years’ War happened and gave us Big Swede Style (my own label). J.F. Crean explains in his essential, excellent and widely cited essay Hats and the Fur Trade:

Just as the rise of the Swiss-style slashed bonnet throughout Europe marked the end of the Burgundian epoch, so the rise of Swedish international power in the Thirty Years' War (1618-48) was marked by a general European acceptance of Swedish fashion.6

Swedish fashions of the time gave Europe its version of cowboy louche: the cavalier. Crean notes that the “wide brim of the cavalier's hat almost presupposes beaver felt: its broad brim was based on the shape-holding qualities and resilience peculiar to beaver felt.” This requires a lot of animal material. You don’t just use the surface area of the pelt as fabric, you end up combing/destroying it to extract fibers (or felt) that can then be worked into a hat shape (the quality standards and manufacturing abilities have varied, but some figures suggest 10 pelts being needed to make one normal sized hat). For a giant hat in the cavalier style, it’s fair to assume a great deal more animals could be needed for the finished work. Fast forward to the 1600s and beavers have more or less disappeared from their ancestral homes in Europe. As one contemporary noted of the Eurasian beaver trade, "[I]f there are any beaver to be found in Muscovie [Moscow], in Poland, or elsewhere as is rumoured, it must be in too small quantities to be traded.”7

Crean also notes that French-Canadian explorers in 1541 took little notice of the abundant beaver stock in North America initially. Beaver pelts were traded incidentally, but were not desirable on their own (the focus was on pelts for adornment, meaning the nicer furs like ermine used for collars and cuffs). As Crean maintains, it’s only with the “prestige accompanying the rise of Sweden to ‘great power status’ followed by her startling victories in the Thirty Years' War which sparked the demand for beaver.” By 1610, you have corporations and financed expeditions setting out to trap the abundant North American beaver population specifically.8

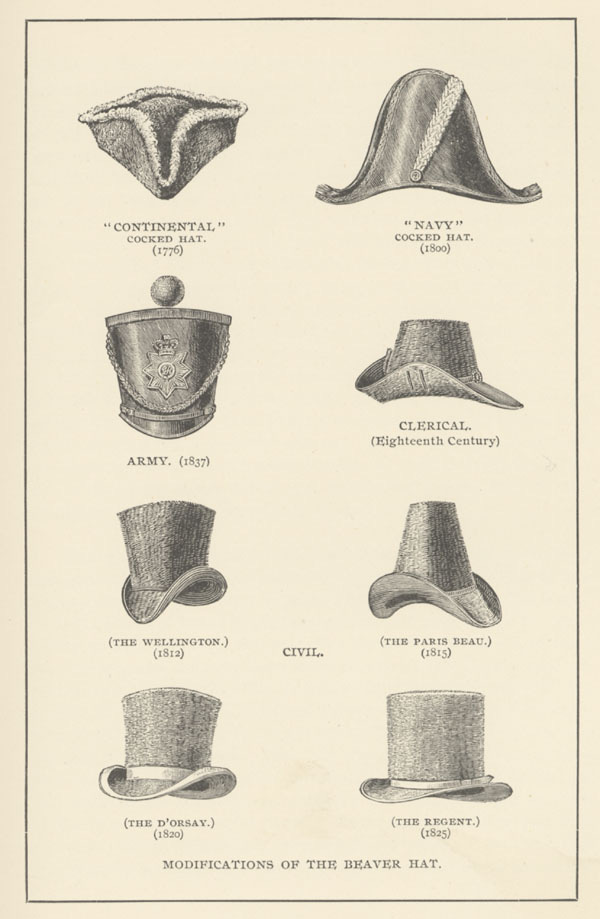

The cavalier hat faded from view and other hat styles gained prominence over the ensuing centuries, but the demand for beaver pelts (and beaver felt hats) remained. Napoleon’s hats, as he always had a set of 12, were all executed in black beaver.9

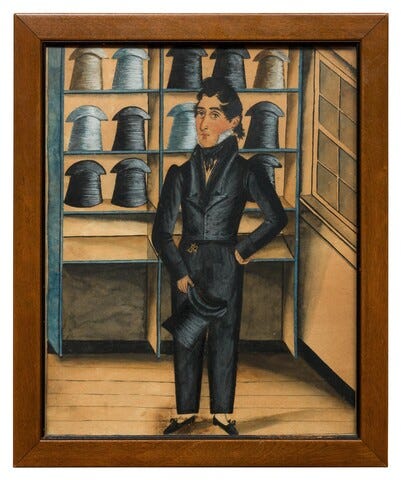

III. Crowning Achievement

The world’s demand for beaver felt would continue unabated, and the trappers and traders of North America would answer the call. As Crean notes, “[t]he discovery of the North American beaver must have been a godsend” to the European hatting industries. Estimates for North American beaver populations stood at around 100-200 million at its height (or 40 million, the numbers growing or shrinking depending on the biases or motives of the estimator), with records showing around 100,000 pelts being trapped/exported per year from Canada (and some years as many as 300,000). The numbers don’t really matter, as this isn’t an economist’s blog where we overly concern ourselves with such things. The takeaway is that we trapped and pelted as many of these animals as we could find for a few hundred years, until we couldn’t find them as easily.

As Crean noted regarding the North American trapping and fur trade industry, its “significance for the development of the Canadian economy need not be emphasized.”10 If this seems unusual to us, we should remember Canadians, especially furriers and other trade specialists reading the essay in 1962, would need no reminder of how their country was wholly built of such frontier stuff. The Canadians have at least one beaver carved into their parliament building (I’ve also been to the Notre Dame du Canada which has a painting of the Virgin Mary holding a maple leaf, so the Canadians are pretty wild about celebrating their natural resources).

A few sources allege that the North American beaver trapping industry waned with the rise in popularity of the silk hat in the 1830s. The enduring puzzle we are left to tease out is whether beaver hats really fell out of fashion and lost ground to silk alternatives, or whether the increasing scarcity of beaver pelts created the incentives to find and use alternatives like silk in the first place (silk and how this hatmaking technology was possibly lost/incinerated in a feud between brothers to get the spotlight in The Alchemy of the Milliners (II)).

The scarcity of beavers in the United States after the 1830s is supported by the journals and work of the naturalist painter, John James Audubon. Towards the end of his professional life11 in 1843, Audubon set out along the Missouri River to document North America’s mammals for his forthcoming, subscription based work: The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America.12

Audubon eventually arrived at Fort Union, then sitting at the edge of the American frontier on the border between present day Montana and North Dakota. Many of Audobon’s paintings were produced by referencing a specimen of the animal (collected by a trapper) or painted from its living appearance in the field. Beaver had become scarce in that landscape by 1843 and Audubon turned to the assistance of Etienne Provost. A legendary frontiersman and fur trapper, Provost was more than qualified to procure living or dead beavers for Audobon’s study.

This quick detour into Provost’s background is also worth taking to illustrate just how trapped out the Missouri River had become by Audobon’s arrival. For the following description and details of mountain man Etienne Provost, I am indebted to O.N. Eddins13, author of two novels and proprietor of TheFurTrapper.com:

Etienne Provost (Provot, Proveau) was born in 1785 in Chambly, Quebec. Chambly was small farming community twenty miles south of Montreal. Little is known of Provost before he became involved in the St. Louis fur trade. There are indications Provost and Joseph Philibert were in the Arkansas River country by 1814. In 1815, Provost joined the August Chouteau and Jules deMun trade brigade bound for the upper Arkansas and Platte river country. Spanish authorities in Santa Fe arrested the Americans and confiscated their equipment and supplies. The Chouteau-deMun men were held in the Santa Fe jail for forty-eight days before being allowed to return to St. Louis.

A year after Mexico’s Independence in 1821, Provost was in Taos, Mexico (New Mexico). Taos trappers trapped the bayous of the Colorado Front Range, the San Juan area of southwestern Colorado, the Salt and Gila rivers of Arizona, the Green and Duchesne rivers and Wasatch Mountains of Utah.

[…]

Provost discontinued his own trapping after 1830, and started leading the American Fur Company supply brigades to the annual fur trade rendezvous in the Rocky Mountains. In 1834, the B. Pratte and Company bought the Western Division of the American Fur Company from [John Jacob] Astor. Lucien Fontenelle and Etienne Provost led the supply train to the Ham’s Fork Rendezvous. At the rendezvous on Ham’s Fork, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was dissolved…B. Pratte and Company were now the major rendezvous suppliers.

[…]

After sixteen years as a fur trade brigade leader, the 1838 rendezvous ended Etienne Provost involvement with the the Rocky Mountain fur trade…he never returned to the Rocky Mountains. Etienne Provost is one of a hand full of men who was an active participant in the Rocky Mountain fur trade from its inception to its demise.

From 1839 until his death in 1850 Provost recruited new employees for the Pierre Chouteau, Jr. and Company and escorted them to the Missouri River posts each spring. Besides these activities, Chouteau contracted Provost’s services as guide to various private expeditions [… including the 1843 Audubon expedition].

Provost was also by all accounts a huge, round man. One companion of Provost (William Drummond Stewart) at the 1837 Green River Rendezvous described Provost as “Old Provost the burly Bacchus” and “a large heavy man, with a ruddy face, bearing more the appearance of a mate of a French merchantman than the scourer of the dusty plains.” The city of Provo, Utah is also named in his honor, although Provost died unaware of this.

So this is the man Audubon has hired to find beavers, and Provost briefed him on the situation on July 5, 1846. From Audobon’s Missouri River Journals:

Old Provost has been telling me much of interest about the Beavers, once so plentiful, but now very scarce. It takes about seventy Beaver skins to make a pack of a hundred pounds; in a good market this pack is worth five hundred dollars, and in fortunate seasons a trapper sometimes made the large sum of four thousand dollars. Formerly, when Beavers were abundant, companies were sent with as many as thirty and forty men, each with from eight to a dozen traps, and two horses. When at a propitious spot, they erected a camp, and every man sought his own game; the skins alone were brought to the camp, where a certain number of men always remained to stretch and dry them.

On July 19, Provost and Audubon were able to find some traces of beavers, but could not catch any. Audubon notes “Provost was discomfited and crestfallen at the failure of the Beaver hunt.” These failures went on for the remainder of Audobon’s trip.

Audobon (or his collaborators) eventually produced the painting of the American beaver above, but these likenesses were not rendered from any close observations Audubon made in 1843. For Audubon to have observed beaver, we would need to return to a trip he took to Manchester in 1828, where his journal records the following on August 10th:

My usual long walk before breakfast, after which meal Mr. Parker took my first sitting, which consisted merely of the outlines of the head; this was a job of more than three hours, much to my disgust. We then went for a walk and turned into the Zoölogical Gardens, where we remained over an hour. I remarked two large and beautiful Beavers, seated with the tail as usual under the body, their forelegs hanging like those of a Squirrel.

When I saw this reference to head measurements I thought perhaps Audubon was describing his annoyance at being fitted for a hat (which would have been too perfect for our purposes). He was instead sitting for a portrait by C.R. Parker, a middling artist from Louisiana who was in England at the time. As for Audubon and his relationship to hats, we can only note that his work depicting North America’s birds eventually saved many of them from becoming hats themselves.

IV. By Executive Order

One hundred eighteen years after Audobon’s doomed beaver collecting trips with Provost, much of the Western world was still wearing felted hats (with the rise of rabbit felt and other manufacturing breakthroughs keeping such creations possible).

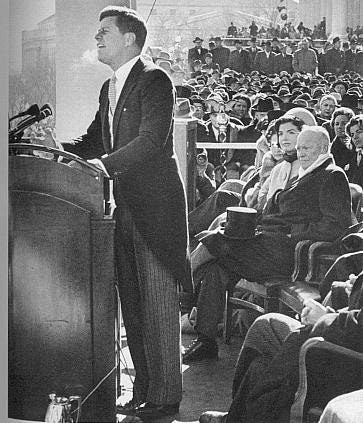

U.S. President John F. Kennedy gets a bad wrap for Marilyn Monroe and the Bay of Pigs. This is deserved. What’s undeserved is the apocryphal and untrue story of Kennedy allegedly ending the hundreds of years of men wearing hats by removing his top hat for his 1961 inaugural address. As the story would render history, because of Kennedy’s decision to speak without a hat on, top hats are now only worn by Roger Stone and attendees to Royal Ascot.

Kennedy wore a top hat to his inauguration, said hat is visible in the seat behind him during his address, and he continued to wear it upon his arrival at the inaugural ball. What is more notable about the day is that Kennedy’s top hat and tails are rather patrician even for his time, and that Eisenhower had some flexing from decades earlier come back to haunt him. Truman wore a top hat at his 1945 swearing in, but Eisenhower elected to wear the more working class Homburg to his own inauguration in 1953. This in turn forced a begrudging Truman, who used to run a haberdashery, to match Eisenhower in hat choice (to avoid any concern of optical/political contrasts of homburgs and top hats). By the same logic and deference for the incoming President, Eisenhower was then forced to carry a top hat in 1961 to match Kennedy as pictured below. Trapped by his own bizarre hat power politics game he started 8 years earlier, Eisenhower looks thrilled.

In closing, we can also point out that Kennedy’s hat in 1961 was, of course, made of beaver felt, rather than the silk “hatters plush,” which requires the labor of silk worms and a lost loom technology we can (possibly) no longer recreate (as we’ll see, the last French factory capable of producing this hat fabric burned down just 7 years after Kennedy’s inauguration).

Internet Bycatch

The trawling net has accidentally grabbed some wonderful specimens the last two weeks.

Happenings

Poolside is on tour for their new album. I caught some early singles and then forgot all about the album coming out (why doesn’t Apple Music remind you when you’ve pre-added an album to your library?).

Mystic Seaport Museum in Connecticut has a display of marine invertebrates rendered in hand blow glass. NYT gave them a write up in November but WSJ alerted me more recently. On display through end of the year.

To Read/Watch

The death of the mall has been greatly exaggerated.

A fellow dad, Sublime Prosaic subscriber and lover of foreign impractical cars gave me the heads up on a Saab 900 go kart auction on Bring A Trailer. Auction ended with the winning bid of $3,600 (something you could probably bid on a real Saab 900, provided it’s in the usual sketchy/gambler condition and not Seinfeld immaculate). This go kart was probably better maintained than either of my 2 Saabs.

Kurt Russell breaks down his iconic characters for GQ. Discussion of Tombstone starts at 9:38. Turns out Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer bought each other reciprocal plots of land near Boot Hill as a parting gift from the film.

Sublime Prosaic is emphatically not about real estate. But here’s a RedFin listing for a $30MM home in Cambria, CA on Exotic Garden Drive. Can channel your inner William Randolph Hearst. Would love to know who built this and why. From one of the architects: “[a]n estate of this magnitude will probably never again be built in California…” A website called the Pinnacle List has an even wilder photo gallery. Wanted: an interview with that muralist.

Luca Rubinacci, third generation at the tailoring house bearing his family name, recently returned from Brazzaville and had this post explaining the distinctly Congolese style of Sapeurs (which in French is a kind of shortening of the name of “The Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People”). This bodes well for the tailoring world in general and we could do with a lot more people wanting to be “ambiance-makers.”

From November, 2022, here is Flume’s cover version of “Shooting Stars” by the Bag Raiders, featuring Toro y Moi. As Flume explains in this behind the scenes feature from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation: “Hardstyle and ripped dudes. It’s a perfect harmony.” Something about Flume standing there doing a kind of Wes Anderson deadpan (other than his saxophone part) makes this incredibly funny to me.14

Beavers are apparently moving northward across the Northern hemisphere, creating beaver dams and helping to thaw permafrost at an accelerated rate. The Russia-Ukraine War complicates the data for the Russian tundra areas, but NASA is able to fill in gaps with satellite imagery. While beaver ponds trap some carbon, the thawing permafrost releases considerable amounts of carbon and methane, so the overall effect of spreading/rebounding beavers is more concerning than it is good news.

As the Illinois Ice Age Museum recounts with a subtext of amusement: “[r]ecent work at a site in Indiana (Swinehart and Richards 2001), though, suggests that their preferred habitat (ponds, lakes and marshes) may actually have expanded as the climate warmed during the terminal Pleistocene.” My money is on us eating them to death.

Otzi the Iceman was found with a hat made from the fur of a brown bear.

Hats and the Fur Trade, J. F. Crean inThe Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science, Aug., 1962, Vol. 28, No. 3. Crean, the son of a hatmaker, will get a bit of a spotlight in later installments, as his work in this niche field is invaluable (or almost stands alone becuase who else is writing about hats with this kind of rigor?). Funnily enough, Crean cites another work for this assertion about the rise of the Swiss style, a 1940 article called The Hat in some kind of journal issued by Ciba (Chemische Industrie Basel).

Quoted from another work relied upon by Crean, L'Art de faire des chapeaux, by M. l'Abbe Nollett, 1765.

One such trapping company, The Hudson’s Bay Company is still with us today (albeit a shadow of its former self) and is Canada’s oldest corporation.

Napoleon’s hat was well known and iconic even in its time. Napoleon’s hatter, Poupard, whose store bore an inscription above the door that translated to “Temple of Taste” was remarked upon by one critic of Napoleon thusly: “[t]he real Napoleon, in the end… is Poupard!”.

I’m thankful to another writer for the apt metaphor, Voyageurs: Beaver Hats are the iPhones of the 1800s. They are just also the iPhones of the 1600s and 1700s as well.

As recounted by Smithsonian Magazine, “…Audubon’s eyesight soon faltered and he started drinking heavily. In 1846, he stopped working and began a slide into dementia. On a visit in 1848, [his collaborator] Bachman was shocked to find that while his friend still looked like himself, ‘his noble mind is all in ruins.’ Audubon died on January 27, 1851.”

It’s a good name, but I don’t know that we can stand for this Sasquatch erasure. It’s possible Audubon did not suspect the existence of this bipedal cryptid. This title would also ignore our own only other North American bipedal mammal, the desert dwelling kangaroo rat.

Eddins has the sort of C.V. I could only dream of and is something of an authority on the history of the fur trade.

Flume’s whole look here also reminds me of that other EDM prankster, Salvatore Ganacchi.