The Garden Aisle feature is about my love of keeping plants in cultivation and other matters I think might be of interest to the hobbyist gardener. This week it’s about cooking with vanished ingredients, genetic drift and what that tells us about deep(er) time. This one has a certain kind of vibe, so at least you have adequate notice:

//

The most LA thing possible I could do is become some kind of clean eating/ethical food evangelist with no forewarning. That’s not what’s going on here. I’m not here to rail against factory or independent farming (how you feed 8 billion+ people is not a theoretical concern), increased vs. heirloom harvest yields, or anything else (I’ll leave that to Monbiot and the rest). The work and goals of farming aren’t something I’ll attempt to adjudicate from my privileged (and by all accounts, unalterable) position of deep ignorance. Sometimes you just read a book that is more interesting than anything else you’ve run into recently, and you have to talk about it. Such is the case with Taras Grescoe’s new book, The Lost Supper.

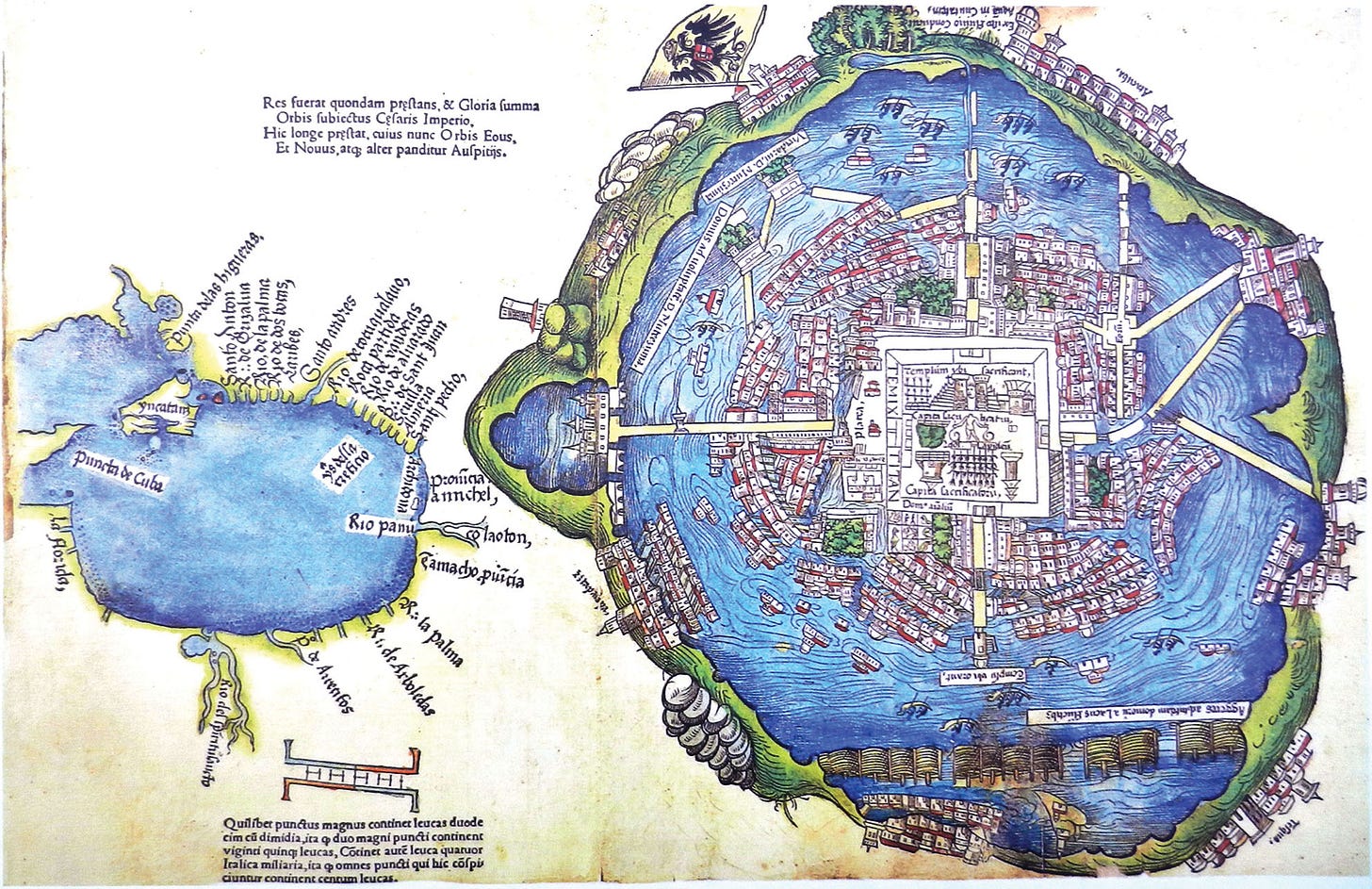

A (re)Movable Feast

The Lost Supper follows the author on a globetrotting exercise in tracking down and eating rare and ancient cuisines. Each food the author showcases has its own chapter and locality: humanity’s first breads, made of emmer and cooked in ovens in Turkey, Aztec caviar (the waterborne eggs of various insects, laid on the waters of the mostly vanished Lake Texcoco), Wensleydale cheese (derived from an endangered British breed of cow)1, a kind of root (camas) that used to grow all over the Pacific Northwest (despite colonial and other observers claiming the original cultivators had no agriculture to speak of), and a few others to be discussed below.

The driving impetus for the author is that our modern foodscapes are suffering from over-engineering, blandness, and an irretrievable loss of complexity (soils degrade, heirloom flavors and varieties are lost in favor of mass market considerations and monocultures, and we suffer in ways we’re only just beginning to understand from all of this). There’s a vague notion at work in the book that the future of our food needs to draw on the collective wisdom of the past. I don’t think this position is self-evidently true (there’s as much inherently bad about our past as there is about the present and near future), but considering how often environmental degradation has caused otherwise large and successful groups of people to disband in our species’ history, it’s a thesis worth considering. We would ignore some of the lessons from antiquity at our own peril. Sure does seem like groundwater is disappearing and soils are getting saltier. Most of our dairy cows in the US can be traced back to two bulls from the 50s and 60s, leading to reasonable concerns about their genetic diversity and survivability in the long term. Just the sorts of things that have continuously created the “mysterious” ruins of abandoned cities throughout our history. Setting aside such sustainability pessimism, I’m still into the book’s messaging for the promised novelty of cooking and eating foods we almost lost.

To put the challenge of recreating ancient foods in context, the author also poses a fascinating question: what would it look to try recreate our modern foods (the recipes of 2023) in the far flung future? For example, if cows (giving us beef, milk, cheese and butter) or bell peppers (the key to cajun food and many other flavor profiles) are extinct and not available to future food archaeologists, what could they make of our recipes and cuisine? It turns out we have a similar puzzle on our hands concerning what ancient peoples were eating.

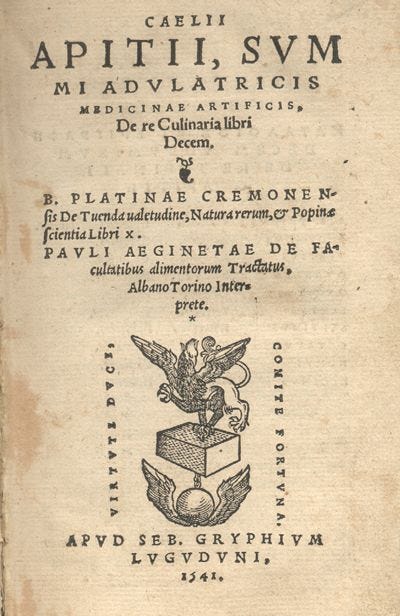

A Greco-Roman cookbook by one “Apicius” (a kind of nickname, meaning something like “the Gourmand”), dated by different experts to be from some time around 100 to 400 CE, has left us with a compilation of over 400 of the Romans’ recipes. As Grescoe points out in his book, none of these recipes mention, or use, something we cook with every day: salt. It’s also not what we think of as Italian food - pastas, tomatoes and a bunch of other things all come later.

Over two thirds of these recipes call for “liquamen” or “garum” (varieties of umami-rich fish sauce we are only now figuring out how to replicate), and many call for silphion, a kind of fennel and a flavor enhancer thought to be extinct for over two thousand years (the Romans possibly did not know how to propagate it, and the desertification of its natural range in Libya and over harvesting did little to help slow its total demise in the first century CE). Setting aside the lost ingredients (some of which can be reverse engineered via chemical analysis from traces found on pottery and other artifacts), the recipes themselves pose a further riddle. Here is one for a hot lamb stew:

Hot kid or lamb stew. Put the pieces of meat into a pan. Finely chop an onion and coriander, pound pepper, lovage, cumin, garum, oil and wine. Cook, turn out into a shallow pan, thicken with wheat starch. If you take lamb you should add the contents of the mortar while the meat is still raw, if kid, add it while it is cooking.

Based on the description, how would you know whether you’ve made something even close to what the original users of the recipe were producing? There’s a whole list of inventions and technologies we’ve lost as a species (you should read that list, it’s one of the best kinds of Wikipedia articles), but it turns out even (seemingly) mundane things like food are subject to this kind of cultural and scientific erosion.

I don’t know if Claire Saffitz’s Gourmet Makes videos will survive the ravages of time, but I worry that future archaeologists will think we were eating soggy Hot Pockets in our Plasticene epoch (if, for example, the crisping sleeve technology of the susceptor gets lost).2 How might a CrunchWrap Supreme or a McRib possibly be recreated? Red Lobster Cheddar Bay Biscuits? What of Baja Blast? Or any other soft drink for that matter? Look on our works, ye [future] mighty, and despair!

Even if these foods cannot be recreated by the novelty seekers of the future, they will at least observe our cuisines to embody one of our age’s central philosophies: a total contempt for the natural world.

What Remains

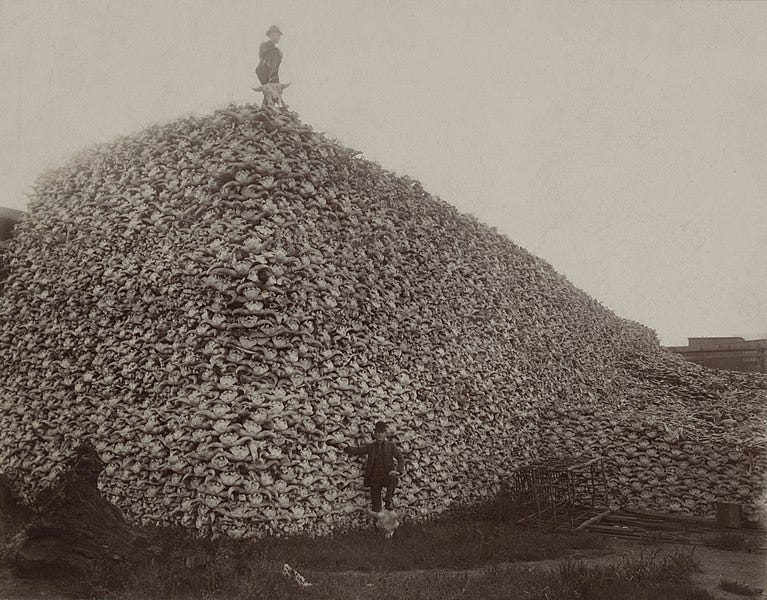

Ken Burns, in doing some publicity for his new bison documentary, has illuminated a point about human consumption I had never quite considered. Namely, no plant or animal can survive the market’s interest in it. Here’s Burns on the subject of the American bison:

[Burns]: There were maybe 60 million, who knows how many, when Columbus arrived. By the time Lewis and Clark are setting out, there are 35 million. After the Civil War, we say 12 to 15 million. And by the mid-1880s, there’s none. The only ones alive are in zoos, or private collections, maybe a few dozen, roaming wild and free in Yellowstone.

[Boston.com]: Even the bones were part of capitalism, turned in for money.

The interviewer interjects at this point to clarify something that was new information for me from the documentary. As American school children, most of us have seen black and white photos of piles of bison skulls. We are made to know, without quite understanding the immensity and scale, that bison disappeared as they were hunted for pelts. A quality history teacher might even bother to point out the special irony of bison leather becoming physical components like pulleys in the bottomless demand for farm equipment, steam engines and other machines.3 What I did not understand prior to watching the Burns documentary is that the market eventually came to rob even the ignominious graves it had made for the bison. At first, observers found it deplorable that the buffalo were skinned of their valuable hides only, with the rest of the animal being left for scavengers. Bad optics, but an even greater desecration was in store. After the hide market cooled (the march of progress/shifting market tastes, alongside there being no more buffalo to find and skin), profiteers returned to these killing fields for the weathered bones as well—carted off to be ground into bone meal for use in fertilizer or as a supplement in cattle feed! Turned into food for the very crops and livestock that replaced the prairie. With the complete disappearance of these skeletal remains, one interviewee likened it to the clean up of a continent-spanning crime scene.

To resume the Burns interview:

[Burns]: As bad as [early conservationist] William T. Hornaday is, he’s right that as soon as an animal is commodified, it’s dead. The beaver almost went extinct because we wanted hats. Plume birds from the Everglades almost disappeared for hats. As William Stegner says, we’re the most dangerous species on Earth and all other species, including the earth, have reason to fear us.

Whether a species is targeted for food or fashion, the result is the same. Incredible pressure is brought to bear on populations where the survivability/viability of the species is a matter of guesswork, or an afterthought. The researchers rediscovering pockets of these surviving lost ingredients like silphion and camas bulbs are rightly concerned about publicizing the locations, lest the market come to gather up the remnants (I’m certainly guilty of immediately wanting to know these locations or where/how I can buy silphion).

We now know what it means for a species to be threatened by overuse or to disappear entirely. If we take a longer view of things and look back towards the Ice Age, there’s a pretty long list of species we’ve eaten to death (our collective review of the planet’s dwindling menu: “five stars, would eat again”). We’re bad at conserving the natural world, but it’s not a new state of affairs. What might it also say about us as stewards if it turns out we also can’t keep the domesticated animals and plants we’ve created from disappearing as well?

“For Nearly 100 Years”

Grescoe devotes a chapter of his book to the Ossabaw Island Hog. A delicious-sounding little oddity. They were dumped by sailors on some barrier islands off of Georgia during the mercantile age (these barrier islands compete with, but don’t quite unseat the Florida Keys as our weirdest American islands). These pigs are remarkable for their genetic similarity to now-vanished varieties from Spain. Genetic information suggests the Spanish picked some of them up from the Canary Islands and dropped them off to let them eat and multiply for harvesting on some future voyage. In the ensuing centuries, the pigs have developed a smaller size characteristic of island animals, but are also now a highly desirable heritage breed (for the quality of their meat, which makes great charcuterie like jamón ibérico, but also as a means of restoring some lost genetic diversity to the pork landscape). Fully grown, they are only 200 pounds (it turns out there’s another heritage breed known as the Choctaw that tops out at 120 pounds, with its genetic diversity/distinction preserved when the owners were forced onto reservations). I became immediately concerned the market might try to come for these breeds and exploit them as true teacup pigs, but then I learned that Ossabaws are highly irascible and unsuitable as pets (Grescoe recounts one farmer’s hog creating a massive head-shaped dent in steel fencing; jury is out on Choctaw pigs).

The island population of Ossabaw hogs are scheduled to be eradicated (they disrupt their island ecosystem by, among other things, eating sea turtle and plover eggs), but breeders have established quite a few herds of them elsewhere. The last hogs were taken from the island in 2002 to set up these programs—the remaining island hogs are left in place due to concerns about transmissible diseases.

In trying to learn more about these hogs, I became aware of the The Livestock Conservancy, yet another weird mailing list I’ve joined as a result of this Sublime Prosaic project.4 I was surprised to learn a domesticated animal could have a conservation status. Ossabaw hogs are listed by The Livestock Conservancy as “critical.”5 That’s basically the organization’s equivalent to “endangered”—less than 500 of something left on the planet (or at least registered by their breeders). One of the criteria for needing to conserve a breed of livestock is a “Long History in the US.” That’s somewhat in the eye of the beholder (few things in America can be old), but the Conservancy clarifies:

The breed has an established and continuous breeding population in the United States since 1925. If developed since 1925, foundation stock is no longer available. If more recently imported, the breed is globally endangered.

Many of these definitions use 1925 as a kind of threshold. I could not discover the significance of this year as of press time, but we can note a population existing for about 100 years constitutes a “long history.”

As Grescoe points out on the subject of the Ossabaw Island pigs, if something has lived on an island for hundreds of years, is it still feral? Put another way, when is a species no longer invasive? What is a “natural” ecosystem anyway if there have been people and their plants and animals living there under cultivation for millennia? Grescoe makes a fascinating point about the dehesa, the manicured oak parklands of Spain. I’ll let Jamon.com pick up the point:

The dehesa is a landscape of beautiful harmony. Holm oak and cork trees, grasses, and aromatic plants thrive in an ecosystem maintained by humans for many centuries as a foraging ground for cattle, sheep, fighting bulls and Ibérico pigs. It is also an especially important reserve for aromatic plants such as thyme or rosemary and a wide variety of wild mushrooms. This exceptional habitat provides a natural and balanced diet to the Ibérico pig, key to achieving the sensory quality of Jamón Ibérico de Bellota.

Conquistqdors, per Grescoe, marveled at the oak parklands of California when they first encountered them. They had stumbled upon a pristine oak savannah that reminded them of the fine ranges set aside for hog pannage of their homeland, but it didn’t seem to occur to anyone that they were traversing another manicured (i.e., not natural) landscape. As Scott Mensing recounts for the USDA in a paper The Paleohistory of California Oaks, what the Spanish were seeing was the New World’s dehesa:

Native Californians lived throughout the oak woodlands and evidence suggests that their practice of frequently burning the landscape influenced the development of the open oak savannas commonly described in the earliest European accounts

Mensing continues:

At least 35 tribes in California used fire to increase the yield of desired seeds, drive game, and stimulate growth of specific plants … [m]ore studies are needed to determine the extent to which Native American use of fire may have expanded oak woodlands in the recent past.

So anywhere there have been people, we’ve set out to remake the natural world for our sustenance. Taking this view, it’s harder to distinguish between natural, invasive, feral and so on—it’s a bit subjective and requires picking winners and losers (which is not to say we can’t or shouldn’t make those choices).

Santa Catalina Island, off the coast of Los Angeles, has recently announced a program to eradicate its remaining mule deer (which were brought to the island only recently, and not by the Chumash thousands of years ago). Residents are upset about this because they like to hunt the deer and eat venison. Catalina Island also has its own bison herd, but they have mostly been subject to population control and the herd is being fazed out of existence by the Catalina Island Conservancy (as far as I know, no one is allowed to hunt them, but please add me to such a list if it exists). This Conservancy is concerned about the overgrazing of rare, endemic plants on the island (the Channel Islands chain used to be connected to parts of Mexico before the ocean’s rise separated them, so there are some fascinating plant descendants produced by the isolation of these islands).

The upshot is that some residents don’t want to trade their mule deer for the continued survival of some plants. As one learned activist asserts for the LA Times, “I’ve never heard anyone say that the highlight of their trip to Catalina Island was seeing a plant no one has ever heard of…” Others maintain “[t]he mule deer have been on the island for nearly 100 years — their gentle presence is an integral part of our island’s appeal…” (emphasis mine). The Ossabaws have a few hundred years on the mule deer, and the mule deer don’t even produce exquisite and rare venison. In a funny coincidence, “nearly 100 years” is clearly nonsense in terms of ecological time, but it might give the deer a leg up should the Livestock Conservancy ever decide to take an interest in the deer.

As someone who grows many Catalina Island endemics as ornamental plants at my home (give buckwheats a chance, you might love them), the idea that they should be food for deer so that people can harvest the venison is preposterous. Even if you’re some kind of environmental nihilist and think only special/charismatic species deserve conservation, you should probably oppose mule deer eating rare island plants into extinction out of your own self-interest. In terms of our modern pharmacopeia, almost all our good drugs come from plants (and mimicking their useful compounds). Even if you don’t care about medicine or finding new plant-derived compounds to treat diseases, letting a plant disappear from the wild is rolling the dice on missing out on the next caffeine, nicotine, psilocybin or mescaline. We also know from getting rid of the browsers and grazers on the other Channel Islands (some of which are protected nature preserves) that it’s good management; there’s been a resurgence of endemic plant life where livestock have been removed from these islands.

All in Good Taste

My hypocrisy on all of these matters should be so obvious as to require no mention. For good or ill, I intend to order some of this Ossabaw ham to try for the holidays (and I am still on the lookout for any way to wear a bison robe in polite society). I fancy myself a conservationist, but what am I actually conserving?

Grescoe spends some time on the plight of Puglia’s olive trees, many of which are over two thousand years old. I’ve seen these trees in person and they are quite arresting. They are the kind of trees that can make you contemplate deep time. The olive trees are threatened by xylella, a bacteria introduced to the region in 2008 when it hitched a ride into the region on an ornamental coffee plant from Costa Rica.

I own three Arabica coffee plants. They are growing happily in a container on my back patio. I purchased these plants from an Etsy grower in a misguided attempt to (i) one day possibly make a cup of California-grown coffee6, having read accounts of others pursuing the same experiment with success; and (ii) out of concern that climate change is threatening the viability of coffee crops globally, coupled with my personal and unscientific belief Los Angeles stands to shift to a slightly more sub-tropical growing region as a net result of climate change.7

I’m growing coffee plants in my parlour like some navel gazing Victorian naturalist, totally heedless of how my buying internet plants from far-flung growers may hasten the kind of global etch-a-sketch erasure of species we’ve set in motion.

California has an oak tree, now threatened by a Jurupa Valley housing development, that is at least thirteen thousand years old (admittedly, it’s been cloning itself to reach this age, but it’s impressive to consider the tree outlasted the Smilodon and the ground sloth), but I’m more fixated on whether I could possibly make a single cup of the world’s worst espresso a decade from now. At least I’m doing my part to set up a refugium population should there be a massive Coffea Arabica die off. To the future food scientists, I wish you luck in replicating the terrible start to finish experience that is the Keurig K-Cup (the lost ingredient is plastic, which you should be able to find in abundance for many millennia).

//

Potpourri:

A much needed palate cleanser for those who scroll to the bottom!

To Read/Watch

Turns out olive oil prices are on the rise. Some people are stealing whole limbs of trees to process the fruit.

Here’s a nice native plant candle collection from PF Candle.

Thanks to Instagram’s rapacious and relentless serving of advertisements, I have learned of Leica’s new home theater system. Given its high price point and coolness factor, I now pass this problem onto you, dear reader.

I’ve been waiting for a bit to recommend one of my absolute favorite public thinkers, Joey Santore. His YouTube channel, Crime Pays but Botany Doesn’t, has influenced a lot of my thinking about and interest in the plant world. It’s a winning combination of profanity, anti-establishment ethos and incredibly solid scientific information. One of his recent videos is a great introductory piece for those who want to know more about his work. Getting into his channel comes with a fair warning. Next thing you know you might be killing your lawn or illegally planting native species in parkways and unimproved lots.

Before reading this book, it never occurred to me a domesticated animal could rightfully have a conservation status at all. What does it even mean for an animal we helped create to be endangered?

Will scholars of the future puzzle at this (now expired) patent for the Hot Pocket crisping sleeve technology?

My thanks to user “beardedhorse” for isolating this excerpt from Tom McHugh's book, The Time of the Buffalo: "Instrumental in the shift to hides was a breakthrough in tanning processes. By 1871, tanners in Europe and America had devised new ways of treating dry buffalo hides, and the hide business boomed. Although the most thickly furred hides, taken in fall or early winter, were still tanned with the hair on for use as robes, coats, or overshoes, the rest of the hides were turned into fine, serviceable leather. One dealer's entire supply went to the British army, which considered buffalo leather more flexible and elastic than cowhide, and used it to replace many of the standard articles in a soldier's outfit. Buffalo leather was also in demand for the belting needed for the machinery of an expanding industrial complex. For interior decoration in affluent homes of the period, the latest mode was richly padded furniture and textured wall panelings, both made from buffalo leather. And for the cushions, linings, and tops of carriages, sleighs, and hearses, it was the best leather available. As the market for the product opened up, tanneries and hide dealers began to broadcast orders for large quantities of skins, and carload after carload started rolling eastward to supply the mounting trade."

I had to answer quite a few CAPTCHA puzzles to get onto the mailing list. Feeling melancholy about seeing the world through machine learning eyes, I discovered others find CAPTCHAS as dystopian/depressing as I do.

As defined by the Conservancy: “Breeds with fewer than 200 annual registrations in the United States and an estimated global population of less than 500. For rabbits, fewer than 50 annual registrations in the U.S., estimated global population less than 500, fewer than 150 recorded at rabbit shows in the previous 5 years, and 10 or fewer breeders. For poultry, fewer than 500 birds in the U.S., with five or fewer primary breeding flocks (50 birds or more), and an estimated global population less than 1,000.”

A similar effort to grow Connecticut Shade tobacco from seed a few years ago was a hilarious disaster.

Whether I am demonstrably wrong about this (and I am) is really all beside the point.