The work of Sublime Prosaic continues.

I. Incendium Magnae

Los Angeles, in the City-State sense put forward by Rosecrans Baldwin (and reality), is really too large to burn. That said, the hillsides and borderlands of the city are especially, and famously, susceptible to burning.

This periodic burning is dictated by geology and flora. Like the Fynbos plant community of South Africa, the chaparral woodlands of California are prone to burning and many of its plant species require fire to propagate.

The question for the human custodians of these places is how often, and how intensely, we want the burning to be. If you want a sense of how predestined the fires in these communities are, here is a chapter from Mike Davis’ Ecology of Fear, published in 1998. The chapter is provocatively entitled The Case for Letting Malibu Burn and it comes with a kind of smoldering hippie righteousness that ages the material unnecessarily (and while the specifics age, the overall point does not, but the tone may still turn some people off of it entirely). As Gustavo Arellano, writing for the LA Times in 2018, summarized the work: “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn is a powerhouse of history, science, Marxist analysis — and a certain amount of trolling.”

Without endorsing any of the politics, I found it engrossing for its compilation of the Malibu region’s history (including arguments for and against its development) and it’s a sobering reminder of how short-term the memories of our communities can be. Saying “we will rebuild” is as much our destiny as the fires themselves. There’s (development) gold in them thar hills.

These ongoing fires, driven by the Santa Ana winds, are routine in one sense. It’s the sort of thing that happens every year (although wildfires here used to have a season, and now any day of any month can be a burning day). What’s unusual to locals is the intensity of the winds. The notion that our densely populated, suburban neighborhoods can disappear entirely is distressingly new information (the 2018 Camp Fire famously erased the town of Paradise in Northern California, but the remoteness and vulnerability of that area have previously made for a spurious comparison). Wildfires usually start in the mountains and canyons (or on the shoulder of some freeway you don’t want to be on), and we all nervously refresh local information sources as the fires are knocked down before they can be blown into larger conflagrations. For local news, there’s a ghoulish balance to be struck between keeping watchers informed about the status of the fires and delivering the spectacle of destruction and misery for engagement and profit. Follow-on small scale human interest stories of loss and heroism are also guaranteed.

Earthquakes, fires and landslides are the known and accepted price of living in the better, wilder parts of our urban-nature interface. Daily beauty is gained, alongside an uneasy acceptance of the corresponding remoteness from safety and resources. This tradeoff between peace and limited ingress/egress is easily illustrated in the Main Street-style of development of some Western ski towns (Park City, Telluride, etc.). Idyllic and tree-lined, with only one way out. Many beautiful neighborhoods in the Santa Monica mountains are similarly situated box canyons. That developers and, until only recently, insurers would endorse and underwrite living in such places lends a veneer of “it can’t really happen here” legitimacy to the massive investments of people and property in these communities.

The peril to the hillside communities is known (and now increasingly priced in), but the larger thesis has always been that the flatland neighborhoods of Los Angeles cannot burn—there isn’t enough fuel down here and the resources of the state, city and country are extensive enough to prevent a humanitarian disaster on that scale from happening. I’ve often exchanged the following sentiment with friends, colleagues and neighbors: “if my house is on fire it means all of Los Angeles is going and we have bigger problems.” It passes for wisdom that my personal circumstances border on irrelevance if the disaster is so unimaginably large that millions of people from the middle of the city are under threat.

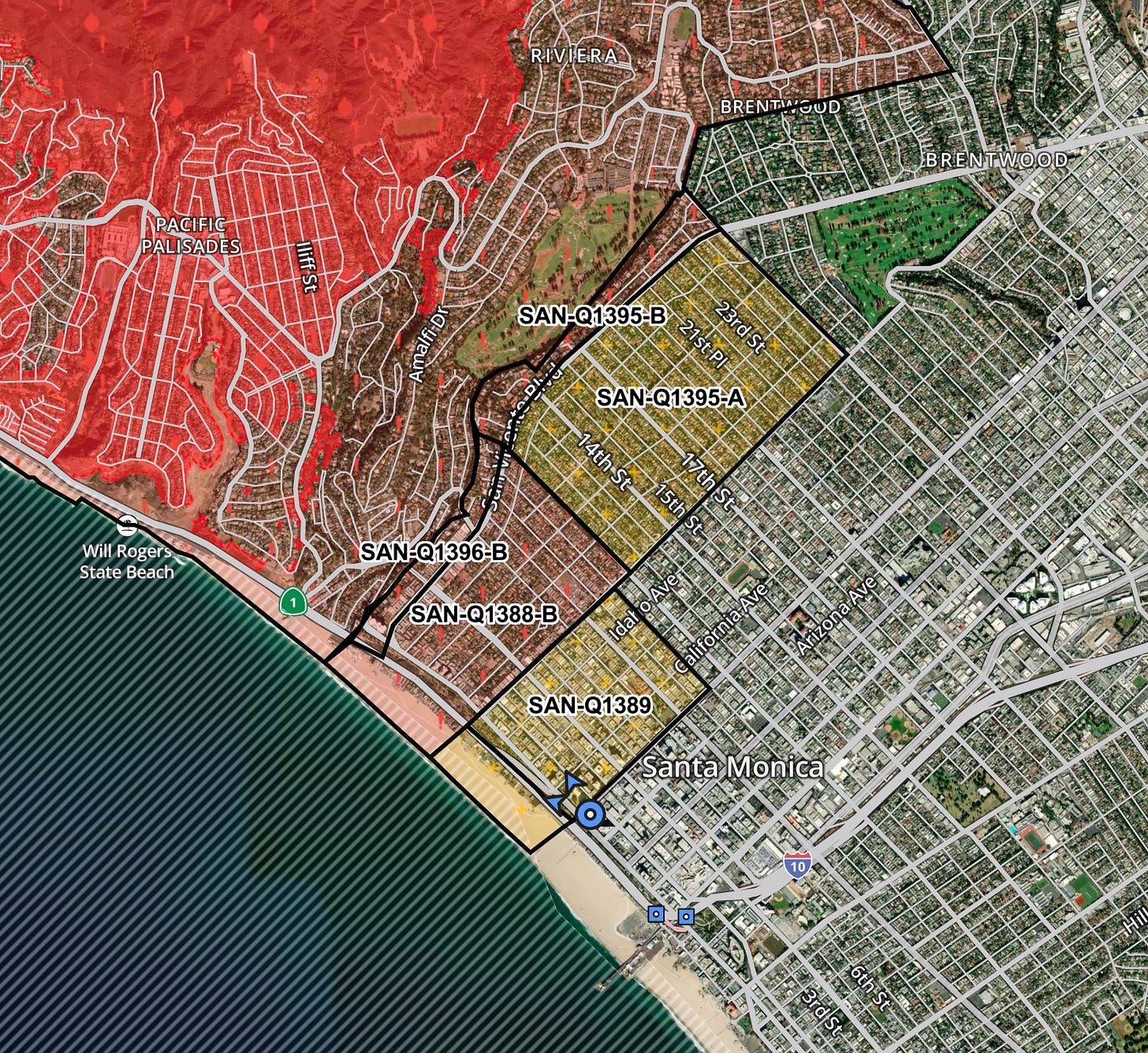

And yet. Here is an evacuation map of the Santa Monica area for the current fires. The yellow squares are evacuation warnings only (so they are preparatory, not mandatory), but they are tellingly also issued for major, dense urban areas. These streets are packed with high rise apartments, luxury hotels, outdoor shopping plazas and some of our best restaurants. In the lower part of the map, you can also see the Santa Monica pier jutting out, which is a major draw for global tourists. That these areas could be affected by a wildfire from the hills is previously unthinkable.

A fire also sprung up in the middle of the Hollywood Hills yesterday, threatening several flatland communities people had assumed were safe as the fire spread in the hillsides above. There’s now a sense that the flatlands, under the right conditions (and with resources stretched thin by competing fires), can also burn. A city fire that jumps from house to house is something from antiquity (Rome, London, etc.), and now also a possible near future.

As for the aftermath, to see huge swaths of homes and businesses in Pacific Palisades and Altadena simply gone is unprecedented, even for a citizenry accustomed to regular incidences of fire. For context, these two areas are on opposite sides of the Los Angeles metropolitan area, about 35 miles and 90 minutes apart from one another by car when traffic is in full swing. As a native Californian, only the Northridge earthquake in 1994 (when I was 6) approaches this in my memory for the scale of destruction.

The intensity of the wind-driven fires meant that these places could not be saved with available resources under the circumstances. In the case of the Pacific Palisades, there’s also an insidious, although not wholly unfounded, belief that a place like this was too affluent to be allowed to burn. If nothing else, the unsparing devastation should help drive home that real estate at any price point, and in any density, is at risk.

I’ve sometimes written here about places like the Getty Villa or the Pedregal neighborhood in Cabo falling into the sea, swallowed whole by nature (the Getty Villa was incidentally just charred a little in the Palisades Fire). Imagining the destruction of things I love or find beautiful admittedly has a strange hold on me. My best guess is that I routinely choose to engage with images like these as a kind of Stoic premeditatio malorum. The thinking goes, if I’ve already imagined beloved (or hubristic) places destroyed by the indifferent forces of nature, maybe I’ll have gained some resilience over these things and the feelings they create when it happens in real life. I’m not sure it has helped, beyond adding a certain glibness to my reactions. On the other hand, it does help me contextualize my all-too-brief life and its perceived problems (that they really aren’t as big or important as the illusion of my self would suggest), but I really don’t really know.

If history is any guide, these communities will rebuild, and some of them will re-burn (hopefully to a saner, lesser degree). We can only enjoy things while we have them, and it helps to remember that there are very few things that we can have for long. I’m also working away on a piece about the importance of incorporating deep time into one’s interior decorating scheme, so this might be influencing my thinking about the impermanence of everything.

It remains to be seen whether this will be a period of temporary decline for Los Angeles and its perennially sunny forecast of itself, or the advent of something newer and more permanent (whether diminished or resurgent).

II. A Worthy Cause: Wellema Hat Co

People lost homes and businesses and there will be a surfeit of worthy causes in the weeks and months to come. For now, I’d like to bring attention to a GoFundMe campaign for Cody Wellema and his family. Cody is the proprietor of Wellema Hat Co, an excellent independent retailer and maker of hats, in Altadena.

As independent retailers go, Wellema Hat Co was truly great. In working with Cody on a hat commission, I found him to be knowledgable, personable, and incredibly responsive.

Here’s a photo of the straw Milan hat he created for me (the idea was to have something more robust than a Panama for my use in the pool, etc., as my Panama hats kept getting trashed and replaced). I am assuming Cody and Co will come back stronger than ever and eventually be ready for new commissions. In a world of giant hat brands (the likes of Borsalino and Stetson), I’m happy keeping my head with a Wellema.

III. Not Famous Enough: Bobby Fingers

A friend recently recommend a channel on YouTube. He was very insistent (even texting a reminder about it hours later) and now I know why. Bobby Fingers is a wildly unhinged lunatic, and his work belongs in The Louvre.

Like all great multimedia performance art, it’s at first a little hard to describe Bobby Fingers (which is a stage name/psuedonym). As an overview, he makes incredibly intricate dioramas of moments in popular culture history (like Steven Seagal getting choke slammed by legendary stuntman and fight instructor Gene LaBell) and then buries them in the wilderness and releases videos documenting his process, interspersed with clues in them so his patrons can find, dig up and own the completed pieces.

In addition to being incredibly skilled in miniatures, he is also a gifted comedy writer (judging this purely from his work in the videos) and a talented musician (he is the frontman in an Irish dance band, King Kong Company). His track pants-wearing character also seems to compel his collaborators in these diorama projects to help him with a mixture of threats and violence (often needing to resort to further acts of intimidation to get his collaborators to turn over their agreed-upon part of the work to him).

His videos are narrated with the breathy, deliberate monotone narration befitting a serial killer. It’s ASMR, but with the vaguely menacing Irishness of his manner of spoken English. It’s like Bob Ross levels of relaxation, mixed with the profanity of an insult comic.

Here’s a sentence I made up composed of some of his stock phrases.

Brendan board. Husband paste. Effluent. A lick of paint and a little bit of lighter fluid to knock back the tool marks.

He is making deranged, beautiful, all-consuming art.

There’s craft here that’s way out of proportion to the subject matter. His method is to first sculpt a life-size replica of someone’s head, then 3D scan that full size portrait and then print it in miniature for inclusion in the diorama. Here is his sculpt of Fabio, for the project depicting the time Fabio was allegedly stuck in the face by a goose during a promotional roller coaster ride.

There’s also insanely high production value in the videos about the dioramas. For Fabio and the Goose, Fingers enlisted Adam Savage (one half of the Mythbusters duo) and some slow motion camera specialists to document firing geese made of ballistics gel at a simulacrum Fabio head (to determine whether Fabio was struck by a goose, as legend holds, or whether a piece of camera struck Fabio instead, as the model claims). The results are otherworldly kinds of grotesque (and suggest that Fabio would be dead if he was struck by a goose).

As a commentator, Fingers also brings an insider-outsider perspective on the film and television industries, and its American-produced/exported pop culture products. His skill with model making means he’s someone who works in the industry, but is just far away enough from the insane epicenter to have insightful and funny things to say about our weak, decadent monoculture.

For his diorama depicting Michael Jackson being set ablaze during the filming of a Pepsi commercial, he decided to cast Jackson’s miniature in bronze, perhaps to reflect the incredible impact Jackson had on him as a youth growing up in Ireland (or bronze is a more suitable material to serve as a brazier, so the miniature can reliably and safely be set on fire). People in pagan ritual attire also show up and play horns in a Michael Jackson-style song Fingers performs as an outro for the video.

I hope you enjoy.

[Bobby Fingers-style voice]:

I’ve ended this Substack post by sculpting your face in 1:1 scale, using water based clay. I’ve used a cutout of your profile, to set the proportions.